An Operation Warp Speed for Better Addiction Medications Can Help Us Escape the Crisis

Why does the United States put so few resources into developing new medical treatments for drug abuse when the ongoing financial, social, and medical costs of addiction are so shockingly high?

We Have a Big Problem and We’re Not Making Progress

Americans are dying of drug overdoses at a level we’ve never experienced before. Despite decades of efforts and trillions of dollars spent on the drug war and treatment efforts, the problem has become much worse.

Deaths are just the tip of the iceberg: the tremendous human and economic costs of addiction, along with the spillover effects of the drug war, corrode society at a deep level. We lose millions of years of healthy lives to addiction, families and neighbors torn apart; toxic impacts from every angle of the drug war including cartels infecting entire governments; and crime, distrust, stigma, and alienation in our communities. Addiction, and how we’ve managed it, has ripples of negative effects unlike any other disease.

Overdose deaths in the United States have risen from about 5,000 a year in 1970 to 20,000 by the year 2000 before exploding to over 107,000 a year in 2022 (rising from about 1.3 to 33 deaths per 100,00 people (CDC)). With so many of these deaths occurring in young people, the years of healthy life lost are staggering.

Thousands of anti-smuggling, policing, policy, and treatment interventions have been run at all levels of the US government. Fentanyl is so much stronger than heroin that smuggling is virtually impossible to stop.

The Golf Ball Problem

I did some math, and found that you can fit more than 8,000 doses of fentanyl inside a single golf ball that you could send through the regular mail mixed into a pack of regular golf balls. How can the government find and stop that? You could fit 37,500 doses of fentanyl in one of those little travel toothpaste tubes.

I call this “The Golf Ball Problem” and I made this ridiculous image with Midjourney to help it stick in your head:

Social programs of all kinds are being tried— rehab, harm reduction, prevention education, therapy, prescribing rules, Naloxone access, recovery medications like buprenorphine, naltrexone, and others, and probably everything else you can think of and have heard of. Most of these efforts have made a difference— the problem would be dramatically worse without the constant vigilance and tireless efforts of friends, families, volunteers, therapists, civil servants, social workers, policymakers, and many more. We can and should be doing much more to give people easy and judgment-free access to treatments like Suboxone and methadone.

But sadly, there’s no city or state, no matter how liberal or conservative in its opioid policies, that has cracked the code and dropped their addiction and overdose rates dramatically or sustainably. The heartbreaking reality is that while much of what we are doing makes a positive difference, we have yet to find a real solution that can turn the tide. When you expand to include the cost of addictions to alcohol and cigarettes, you add another roughly 620,000 avoidable deaths per year just in the US and over ten million globally.

Addiction’s Medical Impact Is On Par with Cancer and Heart Disease

While addiction and overdose are widely seen as a crisis in the US, the scale of the impact is still unappreciated in news coverage and policy circles. The World Health Organization estimates that in terms of disability-adjusted life years (a combination of years of life lost to death and years of life lost to disability) drug use disorders rank second in the US, just behind heart disease:

This data is from 2019 and overdose deaths have risen about 50% since then.

The direct medical impacts of drug addiction and overdose are on the scale of heart disease and cancer, yet the public and private sectors combined spend roughly 95% less on the development of new medications for addiction as they do for heart disease or cancer. Major pharmaceutical companies simply do not pursue treatments in this area. And these massive direct medical impacts do not include the tremendous family, community, and societal costs of addiction, overdoses, and the drug war.

Addiction Hurts the Whole Family, Community, and World

Soon I’ll get to what I think can be done. But I want to emphasize a couple more points about how massive and toxic our addiction problem is, in ways that get harder to quantify.

Think for a moment about someone you know who has or had serious heart disease and then about someone you know who has had serious addiction problems. How did each disease affect the families and relationships around that person?

Heart disease and addiction are both non-infectious diseases, partially or wholly influenced by behavior. Both can lead to death, sometimes quickly and sometimes slowly. But the cascade of negative impacts that radiate out are vastly higher and more painful for substance use disorders. When someone you know has serious heart disease, it can be devastating for themselves and their family, but it doesn’t turn us against each other. Heart disease does not rip families and relationships apart the way addiction does, and it does not spill over into a cascade of negative impacts for entire communities and countries.

Addiction Costs Us $1.5 Trillion a Year: What are We Getting for Our Money?

The financial burden of addiction and overdose on the US is tremendous. The U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee estimates that “the opioid epidemic cost $1.04 trillion in 2018, $985 billion in 2019 and nearly $1.5 trillion in 2020”. That’s a massive amount of economic damage. But it’s even more daunting when you consider that despite all that spending and all the programs and policies and efforts and struggles and suffering that that number represents, the problem is still getting worse. When something costs you a trillion and a half dollars, it would be nice to feel like you were at least making progress. With heart disease and cancer, the costs are painful and the research is expensive, but we can see that better and better treatments are arriving every year.

Four Potential Paths Out of this Nightmare

How can we finally escape this devastation? I think there are four general pathways for progress, one of which we have been virtually ignoring.

Strategy 1: Stop the Flow of Drugs

Can we manage to stop, or nearly completely halt the illicit production, sale, and consumption of opioids and stimulants? The drug war attempted this (is attempting this) and it hasn’t worked well: in recent years, smuggling has become much harder to stop because fentanyl is roughly 40 times more potent per gram than heroin which means it’s 40 times smaller (Int J Drug Policy).

Here’s one tidbit that I think illustrates the trap we’ve been stuck in with the enforcement strategy. Just recently, California put out this statement, “Governor Gavin Newsom today announced that the California National Guard (CalGuard) supported counter-drug operations in 2023 that led to the record seizure of 62,224 pounds of fentanyl in California and the state’s ports of entry. Since 2021, fentanyl seizures supported by CalGuard have increased by 1066%.”

And they added, “The amount of fentanyl seized in California in 2023 is enough to potentially kill the global population nearly twice over. According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, a lethal dose of fentanyl is 2 mg.”

There’s something very off about the proud tone of this announcement. A National Guard Major General is quoted saying, “These extraordinary seizure statistics are a direct reflection of the tireless efforts of the highly trained CalGuard Service Members supporting law enforcement agencies statewide.” And yes, this is definitely an impressive amount of very, very difficult work. But… if the amount of fentanyl seized is up 1,066%, don’t you hear a teeny tiny little voice in the back of your head screaming “that probably means smuggling is way, way up!”

Imagine if you got an email from your kid’s school that said “Thanks to the tireless efforts of our staff, seizures of knives from student lockers were up 1,000% in the past three years.” Would that make you feel like things are going great at school?

This doesn’t mean that attempts to stop smuggling or to stop production of fentanyl in other countries don’t make an impact— they probably do have some effect on keeping prices up and, as we’ve seen with cigarettes, price does make a difference towards reducing addiction. But the street cost of heroin / opioids has fallen 80% since the 1980’s and meth prices have been falling significantly over the past few years. At some point these drugs become bottled water: the water itself is almost free and you are just paying for the delivery.

It’s clear that stopping smuggling and access to addictive drugs is not a path towards a real lasting solution and the negative effects of the drug war have been horrendous. We’ve been doing essentially the same thing for 50 years and the problem has grown worse. The degree of constant surveillance, invasion, and control of people’s personal lives that would be required to truly end access to dangerous drugs in the United States would never be accepted by Americans, nor should it be. We are not and should not be China or Singapore. In a society with as much social heterogeneity as the US and with as many personal freedoms, it is just not possible to stop the inflow of large quantities of addictive drugs.

Strategy 2: Public Education and Convincing

Another way that we could solve the addiction crisis is if we can manage to educate, coax, and convince people to never take illegal drugs. Like our efforts to prevent smuggling, anti-drug education and public messaging has been deployed decade after decade, and the problem is still getting worse. There’s no doubt that public awareness of the risks and dangers of addiction makes a difference— most people avoid these drugs completely because they are afraid of the risks. Use of cigarettes and alcohol in young people has fallen, partially because of health information and awareness. But education is not a realistic path towards ending the opioid or stimulant crises or in protecting future generations from whatever new drugs may come along.

That being said, drug epidemics, like the crack crisis in the 80’s, do sometimes rise and it seems that cultural factors play an important role in the fall. Perhaps there will be a gradual culture shift in our era, as people become aware of just how dangerous fentanyl is, and maybe this will reduce the problem. Frankly, this seems unlikely given the strength of the opioids on the market and the cheaper production methods, but even if it did occur to some degree, it would not protect us in the future. Cultures that can change can also change back. Cultural memory of the horrors of a drug epidemic fades as the generations roll on and drugs often make a comeback.

Strategy 3: Expanding Existing Medication-Based Treatment Programs

For opioids, medication-based treatment programs, using medications like Suboxone and methadone are the state of the art for reducing addiction and overdose, but they have been tangled in culture wars and unnecessary restrictions. Lev Facher’s War on Recovery series at STAT shows just how broken the methadone treatment system is in the United States. There is a growing consensus among doctors, clinics, and advocates that we need to make it much easier for people to get methadone and buprenorphine whenever and however they want it. I agree wholeheartedly. We should also open safe injection sites across the country to reduce overdoses and connect people to treatment options, though it will be politically challenging to do so.

On top of these approaches, ‘contingency management’ systems, like the impressive DynamiCare Health mobile platform, give patients rewards for continuing treatment and passing regular drug tests. Contingency management has been validated in dozens of studies and dramatically increases treatment success, but needs to be scaled beyond pilot programs.

While we need to do much more with the tools we have now, existing opioid treatment medications are complicated, have serious side effects, and their use has been and will probably continue to be limited by challenges onboarding patients to these treatments, relatively low retention rates for these drug classes, and, most importantly, intense resistance to methadone in many parts of the country. The methadone battle has been going on as long as the drug war and now private equity companies who own methadone clinics are fighting against anything that would make it easier for people to get methadone outside of restrictive settings. Medications for alcohol addiction have seen similarly limited use and current medication options for stimulants like cocaine and methadone are not great.

Ultimately, the medications that we currently have available to providers are not as good as they could or should be– we need to get better tools in the hands of doctors and patients and we need medications with high retention rates that can scale nationally and globally without huge culture wars.

The rise of fentanyl has made this lack of good medical options even clearer.

Existing medications for addiction and overdose are less effective for fentanyl. Research on opioid treatment effectiveness from more than 8 years ago, when fentanyl was relatively rare, may be inaccurate today when fentanyl dominates overdoses, because fentanyl is significantly different from heroin:

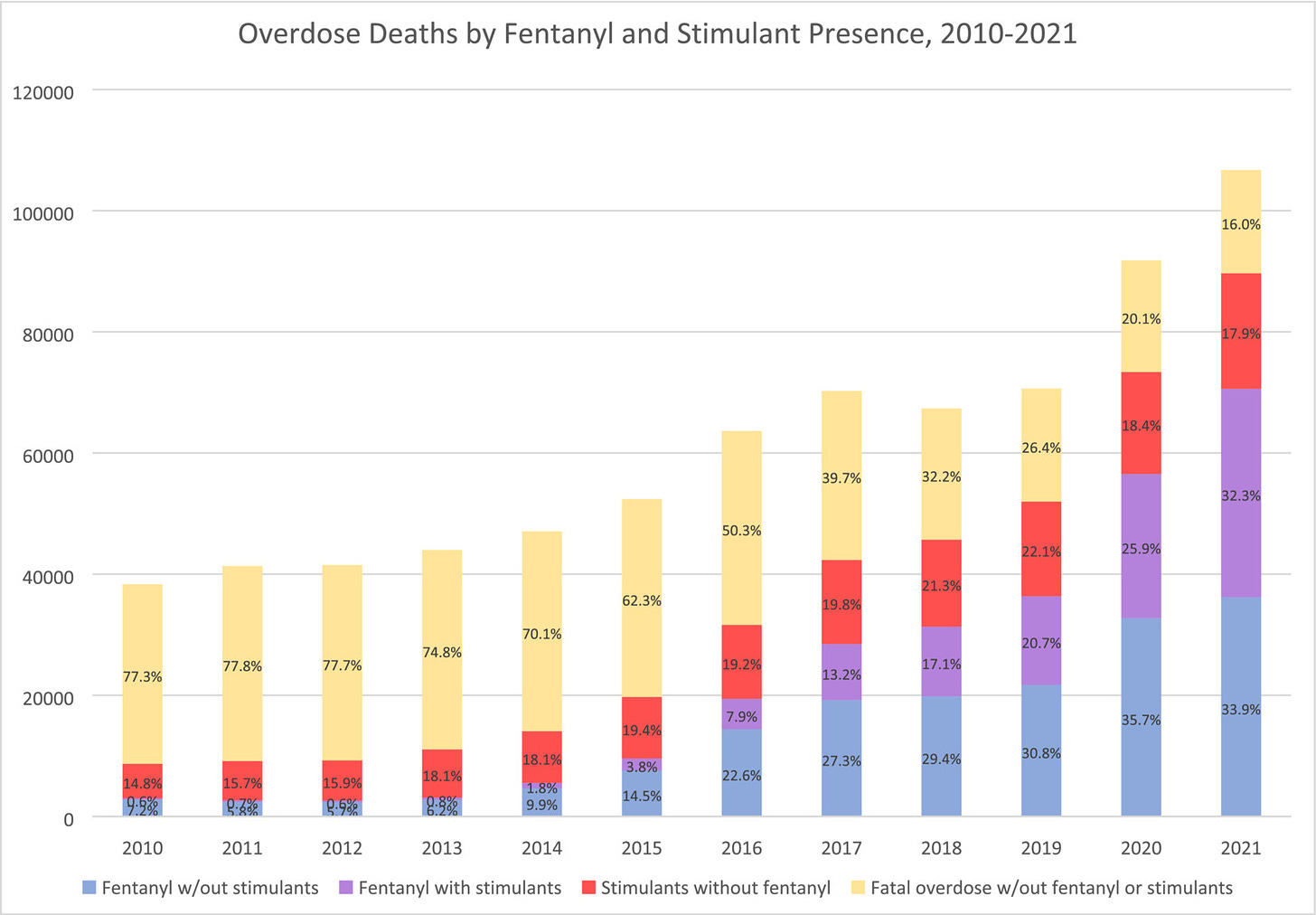

Fentantyl is so much stronger than heroin that it is easy to combine with other drugs and now a huge percentage of current overdoses are intentional or accidental drug combinations, see the chart above.

Fentanyl wears off more quickly, so people who use fentanyl redose more times per day than heroin and often combine fentanyl with methamphetamine to extend the time before they need to redose.

Fentanyl is ~40X stronger than heroin so it is much, much easier to accidentally take too much and overdose.

Naloxone, aka Narcan, reverses opioid overdoses but doesn’t work as well with fentanyl compared to heroin (a better option is becoming available now).

In addition to the limitations of existing treatment medications, some rehab strategies that showed promise for heroin addicts— long-term support while waiting for a person to choose treatment— could be counter-productive today when fentanyl is killing so quickly that many people die before ever becoming a long-term user.

Strategy 4: Develop Novel Breakthrough Medical Treatments

I believe the centerpiece of any long-term, sustainable solution to addiction will be the development of new breakthrough medical treatments for addiction. There are some incredible new treatments in early stages like opioid vaccines, GLP-1s, and non-addictive painkillers, and we will need a major push to get them available at scale. It’s doable and would be a truly world-changing achievement.

Medical Breakthroughs Happen

The history of medical science is a history of miracles, from vaccines to antibiotics to HIV drugs and hundreds of other incredible achievements. Intractable medical problems get solved every year, sometimes incrementally and sometimes in massive leaps.

In just the past couple years, we have seen remarkable medical advances. The first cure for sickle cell anemia came to market, achieved through gene therapy. When COVID appeared, we developed new vaccines using brand new mRNA technology and got it to market in record time, faster than the most knowledgeable experts said was possible. We’ve also seen the first wave of effective and life-extending drugs for obesity— an intractable medical challenge for a hundred years, a problem that people said ‘can’t be solved medically’ and that suddenly has an effective treatment.

Meanwhile new immune therapies for cancer are making tumors disappear magically with zero side effects— they work for a few cancers already and more of these therapies are arriving all the time (like this report from just two days ago). Even for malaria, which evaded vaccine efforts for many decades, there are finally effective vaccines available that will save millions of lives.

There is absolutely no scientific or medical reason that we can’t achieve similar breakthroughs for addiction and overdose if we put money and focus towards developing radically better medications. We could functionally cure substance addiction, both for individuals and for society, if we try.

Medical Breakthroughs Happen Faster When We Try Harder

As we saw so clearly with mRNA COVID vaccine development, when there is intense focus and a surge of funding for an urgent medical problem, things can happen faster than even what leading experts believe. This excellent article by Tim Hwang at IFP examines why mRNA vaccine progress was ignored for decades before the funding and scientific efforts that suddenly made them real. Here’s a great quote:

“Economists preparing recommendations to the White House on allocating funds towards different COVID-19 vaccine methodologies received feedback from some corners that investment plans positing a possible role for mRNA were fanciful.”

As an even more apt example, the belated, but eventually vigorous, efforts to understand and treat HIV, perhaps the most frustrating virus ever researched, is another incredible example of the medical science community tackling in a few years what had appeared to many as an impossibly difficult problem.

Medical Breakthroughs Are Cheap Compared to the Downstream Costs

Compared to the Congressional estimate of $1.5 trillion in annual financial costs we bear from the opioid crisis, bringing new pharmaceuticals to market is an incredible bargain. Once a treatment is discovered, we have it in our toolkit forever. The cost savings and economic benefits of even a modest reduction in addiction are massive (we will be exploring this in more detail in future articles).

The US spent approximately $18 billion on Operation Warp Speed, which supported development of 6 different novel COVID vaccines and brought them to market in record time. $10 billion of that expense went to purchasing doses of the resulting vaccines, paying ahead of time for Americans to receive the vaccines for free once they were ready. Far, far more people die in the US from addiction to opioids, alcohol, and stimulants every year than COVID at its peak, yet we only spend about $500M a year on new medication development, with virtually no pharma company help. The scientific path forward is not as clear as it was for COVID vaccines but it will be if we invest in the problem.

Just to reiterate, for our simple human brains that can’t really process a number like $1.5 trillion, that’s 1,500 billion dollars per year in direct and indirect economic costs from addiction. Could we afford to spend $10 billion per year on developing new medications that would help save us a huge chunk of that $1,500 billion per year? To answer that, here’s a visualization I made:

Not only can we afford to spend more on medication development, but it would be financially reckless not to.

Medications are an extremely low cost intervention for addiction, when they work. Shelters, rehab centers, emergency rooms, prisons, and social and outreach programs for addiction are extremely expensive. Families and medical systems often spend hundreds of thousands of dollars per person to care for people with addiction and we aren’t getting great results. As a general rule, social programs are very costly compared to even the most expensive medications because they require so much time from so many skilled people, day after day. And at a personal level, imagine if you had a family member who was severely addicted to opioids or alcohol and you knew that there was a great medication option available rather than a $35,000 a month rehab center that could bankrupt your family and has a terrible record of success.

Breakthrough Treatments are Already in Development

There are remarkable efforts in progress to develop individual and combination vaccines that can block fentanyl, oxycodone, cocaine, meth, and other drugs. Shots are going into arms already. There are new antibody therapies being studied to reverse and prevent overdoses.

There are non-addictive painkillers in the pipeline, including this new one from Vertex, which in early 2025 could become the first strong non-opioid painkiller on the market. A powerful non-addictive painkiller like this could prevent a portion of new opioid addictions from starting if it is used to replace opioids after surgeries and other medical treatments. It could also prevent diversion of prescription opioids to other people and it could be used to transition long-term pain patients off of opioids. (I’ll be writing more soon about the market failures that might keep non-opioid painkillers from scaling and how we could solve this challenge.)

And there are some incredible studies happening on directly reducing addictive drive with the same GLP-1 medications like Wegovy and Ozempic that are approved for diabetes and obesity. These drugs could become revolutionary in the field of addiction and they are already FDA approved and available to doctors, which puts them years ahead of other new treatment options.

Multiple human studies of GLP-1 for alcohol abuse, smoking, and other drugs are underway, and the drugs have already been shown to work in animals. In humans, a small, randomized controlled trial recently showed a huge drop in opioid cravings for people given liraglutide:

“Among 20 patients for opioid use disorder, those on liraglutide experienced a 40% reduction in opioid cravings over the three-week study, with this effect evident at even the lowest liraglutide dose, according to data presented here at the American Association for the Advancement of Science conference.”

As I covered in our recent news roundup, a new study from Rong Xu, Nora Volkow, and others shows a 40-60% drop in cannabis addiction among people who were prescribed a GLP-1 drug for diabetes rather than a non GLP-1 drug, and this is occurring simply as an unexpected side effect of the medication. It’s an incredible finding and additional papers from the group on GLP-1 impact on alcohol and opioid addiction are coming soon. Remarkably, GLP-1 drugs also appear to dramatically reduce suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety.

The stories people tell about their addictions disappearing as a side effect of taking a GLP-1 for diabetes are dramatic:

“Booze noise is absolutely a thing. And it is ABSOLUTELY GONE. Period. I almost want to cry typing this…I haven’t had a drink since October 26, 2023. Miracle! I tried one quick swig of raspberry vodka (don’t ask-lol) on November 20 and it tasted like pure gasoline. That’s it.

Started compounded semaglutide on October 18 at the usual .25 dose. Had several White Claw seltzers the following week and then literally started to lose interest. Unbelievable! This is the longest I’ve gone without a drink in probably more than 22 years.”

Many, many more amazing personal stories are here.

My recent article, Ozempic is Showing Us That a Cure for Addiction is Possible, captures why I believe that demonstrating a broad reduction in addictive drive is such an important milestone for the field. The science is ready to move forward but it takes a lot of money to bring treatments through large scale trials and get them to providers.

Progress Is Slow Due to Lack of Funding and Pharma’s Absence

"We've never considered addiction as a disease that is worthwhile to invest in, despite the very high rate of mortality. We need to change those priorities. We need to see that if we don't tackle the problem of addiction — if we don't treat [it] like other diseases, we are going to continue to face this horrific epidemic of deaths." - Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Major medical advances that can substantially reduce opoid addiction and resulting deaths are clearly possible, but the progress that is happening is moving very slowly because there are so few academic teams and companies working on addiction medication development.

In an interview with STAT, Nora Volkow, the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse said on GLP-1s, “The data looks very, very exciting” but she also pointed directly to the obstacles:

“The pharmaceutical industry has never spontaneously embraced us and said, ‘We want to help develop treatments.’ No, no, no,” Volkow said. “We go to them …. and say, please, please, we have an obligation.”

Pharmaceutical companies, who are currently necessary to fund the major studies needed to bring drugs through FDA approval, have not made addiction and overdose a high priority because the size of the market opportunity is difficult to predict, the costs of getting psychotropic drugs through trials are much higher than other drug classes, and the risks of working with vulnerable populations scare their investors.

As one pharma executive told me, major pharmaceutical companies are afraid to run trials for people with addictions or mental instability because there is a risk that adverse events like suicides could occur during the trial and unfairly damage the reputation of the medication or the company. Why would you risk your existing revenue stream from a blockbuster medication like Ozempic by running a trial on Ozempic for addiction? This is a severe market failure that we can and must address.

Here are a couple charts from an industry report that show the problem quite clearly.

Is it any surprise that we still don’t have effective non-opioid painkillers on the market? Is it any surprise that we don’t have cures for addiction? The problem is not the science, it’s the near total lack of investment in this disease area.

Considering the central role that Purdue Pharma, the Sacklers, and other companies played in creating the addiction crisis, big pharma should be required to be part of the solution. There should be a public benefit requirement to spend some percentage of pharma revenue to tackle socially complex diseases like addiction, depression, schizophrenia, and suicidal ideation, regardless of the reputational risks and, sure, maybe we could give some liability protection if that helps get trials going. There’s multiple ways to tackle this, but something has to change.

We Need to Dramatically Increase Addiction Drug Development Funding

The government has made only modest investments in research and drug development for addiction because the political will on this issue tends to be mostly reactive— there is money for policing, jail, rehab, social services — because these become obvious and urgent needs in cities and towns all over the country when the medical problem upstream has not been addressed. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) is where the action happens, but it needs more money. NIDA spends about $500 million a year funding development of new medications for addiction and another $500 million on basic research related to the neuroscience of drugs and addiction (budget overview is here). The NIDA pipeline of drugs under development is here. But as a member of NIDA’s committee recently told me, the pipeline of potential treatments is too small and is moving too slowly, “We need more shots on goal.” That means more funding going to more academic labs and small companies.

To take on this crisis fully, we need to dramatically increase federal spending on drug development and research oriented towards development of new treatments, likely by an order of magnitude. And we need to create strong financial incentives for companies to bring drugs to market, as we did with Operation Warp Speed and as has been proposed for new antibiotic development in the PASTEUR Act.

Novel Medications are Good Fiscal Policy

Quite simply, when you consider how bad the overdose crisis is, we should be trying everything that might work. We’re spending mountains of money already on enforcement and treatment. The US currently spends at least $41 billion annually on drug policing and enforcement alone. We can easily afford to increase government spending on addiction research and drug development from $1 billion to $10B a year and create a $5B pool of guaranteed purchase incentives for companies that bring breakthrough treatments to market, so that they will feel more confident pursuing new drugs in this area. $9B a year in new spending for research and drug development is a drop in the bucket of the federal budget, and, if it works, the cost savings and economic benefits will be dramatic. We have every reason to believe that it will work because of the treatments that are already in the development pipeline. The fiscal benefits will be enormous even if new treatments are only partially successful in ending the crisis. I will be going into more detail about proposed funding levels and related policy shifts in future articles.

And to flip this question around a little, wouldn’t it be incredibly wasteful not to make an investment in prevention that could dramatically reduce the $42B we’re spending on enforcement? Why yes, we agree!

We’ve Done This Before and It Worked

In the 1980’s, AIDS was a medical emergency. The disease was baffling scientists, spreading rapidly, and deaths were increasing steadily every year. While cases and deaths mounted, there were politicized and discriminatory debates about what to do and the government response was slow. Activists demanded attention and treatments. Meanwhile, scientists were up against an infuriatingly elusive and mysterious virus, different from any that had come before. Gradually, the US government started investing more and more into research. With this funding, the science advanced quickly— the HIV virus was discovered, antiretroviral therapies were invented, and these treatments were rushed to market, just as deaths were reaching nearly 50,000 a year (half of where overdoses are today). Treating HIV was a historic political, scientific, and medical achievement.

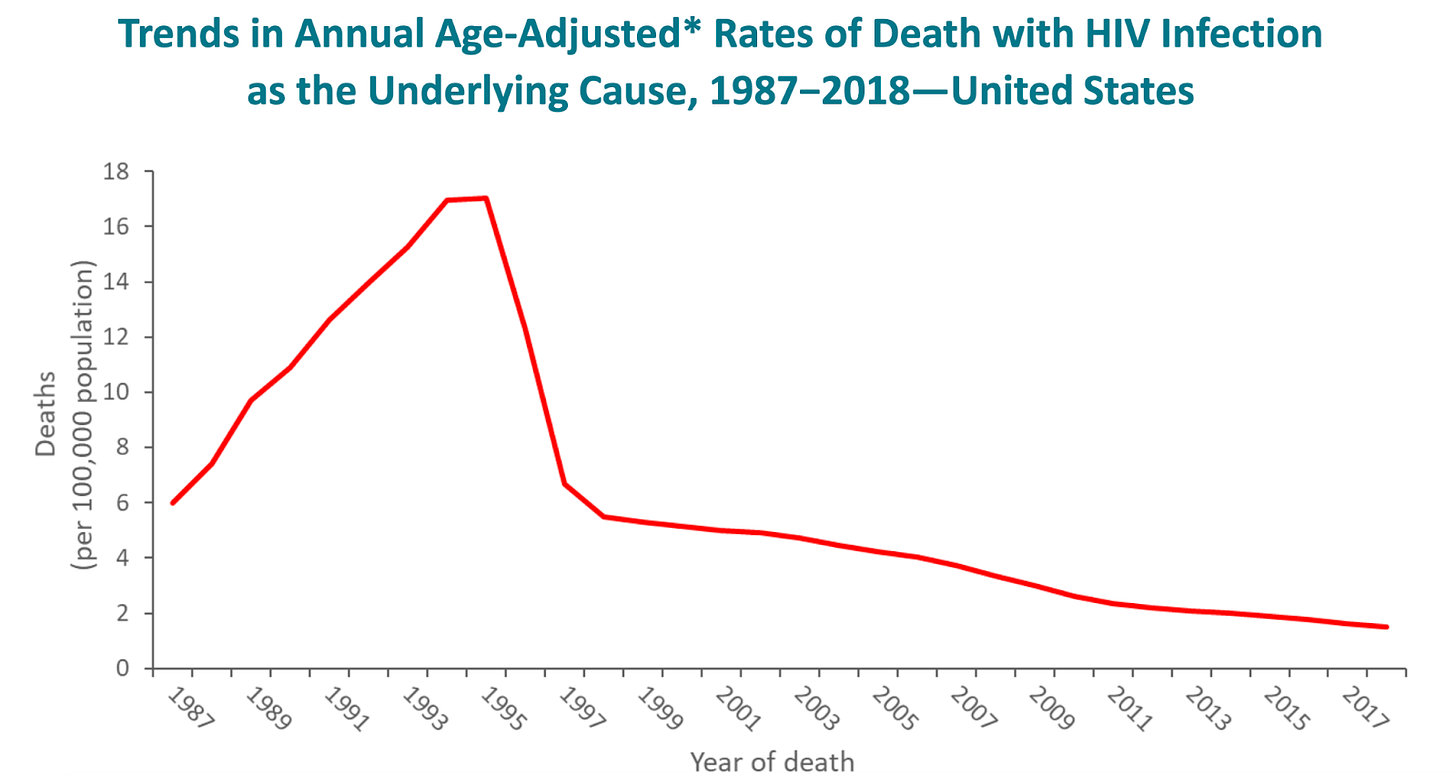

The miracle of the HIV drugs can be seen vividly as the protease inhibitors reach the market in 1995. The drop in deaths when the new drugs arrive is simply astounding:

What made these new miracle drugs for HIV possible was sustained and steadily increasing investment from the federal government focused on finding a cure. The FDA even created the Accelerated Approval Program as a way to safely rush AIDS treatments to market, a program that is now used for a range of diseases and treatments. The emergency was clear, the urgency was clear, the funding was there, and there was a mass effort to get a solution to patients quickly. Deaths dropped from roughly 50,000 a year at the peak to 20,000 within 3 years, a 60% decline. And they’ve declined steadily since as medications continue to improve.

It’s Time for a Major National Effort on Addiction

Opioid and stimulant overdoses are now killing more than twice as many Americans per year as AIDS did at its peak. The urgency of the situation is already clear in every state and city and town in the country. Some of the stigma around drug users has eased and most people and organizations now know that addiction is best understood as a disease. However, unlike every other major disease we face, there is not yet a widespread movement demanding that we “find a cure”. We need to set the bar higher.

I believe there is also a unique political moment happening right now in the US. The drug war has been an extremely divisive and partisan political battle for decades and that has made scientific progress difficult. We’ve all witnessed the failure of efforts to stop smuggling and the futility of arresting low-level drug dealers and I think many people on the right are open to new options, even if we continue existing enforcement efforts. And as we’ve seen liberal cities like Portland and San Francisco veer towards and away from opioid decriminalization, I think many folks on the left are eager for humane solutions that can address the root medical problem itself. Democrats and Republicans are both seeing the devastating impacts of addiction in their communities and we have a chance to put resources towards new solutions that can change the future of addiction forever. Everyone wants to heal.

It’s time to recognize that the addiction crisis in the era of fentanyl has far outgrown the treatment and policy tools we currently have and that we need new medical breakthroughs to turn the tide. Dramatic medical progress happens when we have a shared goal, political will, and the resources that doctors, scientists, and pharma companies need. We’ve done it before with other urgent disease crises, it worked, and we can do it now for addiction.

Postscript: What We’re Up To

We are a small team of researchers, data scientists, and advocates. Our mission is to examine and present the latest work that’s being done in the field, to better understand why this work has been limited in scale and scope, and to try to build a strong case for the public, private companies, and the government that medical research for addiction and overdose must become an urgent national priority. This article is an effort to lay out the framework for our research and a way to think about the problem. We’ll be publishing a lot more detailed analysis, charts, news, and interviews over the coming months.

I want to dive in thoroughly on every aspect of this challenge and present here what we learn. We’ll be writing about:

Weekly news updates on exciting new research and policy developments.

The most promising new medications for addiction under development. Where is progress happening and where is it stuck?

Fentanyl is a disruptive new technology that undermines existing drug policy strategies on the left and the right.

Market failures that have kept addiction and non-opioid pain drugs from getting to market.

How much are we spending on substance use research compared to cancer and heart disease relative to medical need and social impacts?

Where can we find the most bang for the buck with medical interventions for addiction.

Limitations of existing addiction medications like methadone and Suboxone, which are currently the gold standard for treatment but still have very high relapse rates.

Emerging non-pharmaceutical treatments, including contingency management programs, in which people are given frequent small rewards for passing drug tests and sticking with methadone or Suboxone.

The whole story in 10 charts with (almost) no words.

What could the government do to dramatically increase medication development and move candidates through the pipeline faster? What policy models have worked in the past for other urgent disease crises?

Please subscribe so you can read more! It’s all totally free.

And we hope to grow an active community here— the articles that we publish will be living documents and, I hope, useful references for other people trying to understand the crisis and the opportunity. We want to hear your feedback, learn from you, correct mistakes, add helpful context and missing information that you bring us. You can reply to email newsletters or email us at curingaddiction@substack.com.

Getting Involved with This Project

We are also hoping to find more volunteers and allies to join the effort. If you would like to be involved with research or writing or if you have domain expertise here and would like to send us your thoughts, we would love to hear from you.

We are a mostly volunteer effort and particularly need expertise and research collaborators in medicine, statistics, pharmaceutical pipeline expertise, economic impact estimation, vaccine development, and biology. We especially need great science writers! We may even have some funds for part-time work.

We are very eager to connect with more MDs and PhDs who resonate with our approach and are interested in being involved in any way. Even if your time is highly limited, serving as an advisor or ally can make a big difference in our conversations with policymakers.

And even folks without any particular domain expertise can make a big contribution to the project, reading drafts and helping with research and writing. So please get in touch if that sounds fun.

Absolutely, Nicholas. You're on to something here.... Let's keep this conversation going!