Addiction medication sales will explode when better treatments arrive

Why is the disease that causes more deaths than any other still considered a small drug market?

The market for addiction medication is where the market for obesity drugs was five years ago: sales are languishing due to a lack of appealing and effective therapies but the pent up demand is absolutely massive.

Tens of millions of people in the US are addicted to alcohol, opioids, nicotine, or stimulants. This population is at extreme risk of morbidity and mortality. Addiction causes more deaths than any other disease in the United States. Beyond the raw death numbers, most opioid and stimulant overdose deaths happen in people under the age of 50, people who would have many decades of life ahead of them. The burden of disease is huge. Arguably, there is no single intervention that could contribute as much to extending global life expectancy as a medication that eliminates cravings for addictive substances.

Given the large patient population and extremely high unmet need, you would expect that addiction medication would be at the top of the priority list for all the major pharmaceutical companies. Au contraire!

A near total lack of investment in addiction medication development

Pharmaceutical investment in addiction medication development is tiny. The big companies avoid it completely and only a few smaller companies pursue it at all. Medication development efforts have been stalled for decades and even now there is virtually no private investment in the space:

Four reasons pharma doesn't develop new addiction drugs

Market size skepticism. This is perhaps the biggest obstacle and the one I'm focusing on in this essay. There’s a perception that because existing addiction medications don’t sell well, new treatments won't be adopted widely.

Perceived lack of tractability. There have been no major breakthroughs in addiction medicine for decades. Methadone, still considered a crucial first line treatment for Opioid Use Disorder (OUD), has been in use for 50 years. Buprenorphine was approved 20 years ago.

Expense of running brain medicine trials. Brain medicines in general have a low success rate getting through phase 3 compared to other drug areas like targeted cancer therapies. Phase 3 trials are expensive, often hundreds of millions of dollars, and involve complex and subjective measures and unpredictable side effects.

Perceived reputational risk. A senior pharma executive told me that companies are afraid to run trials on populations with opioid or stimulant use disorders because of the risk that random deaths may occur in the treatment side of the study, even if the drug being studied does not increase, or even lowers, suicide risk and mortality. For a smash hit product like GLP-1s, companies fear that bad luck in an addiction trial could taint perception of the drug for other, extremely profitable, indications. (As a side note, it's worth noting here that there is strong evidence that GLP-1s dramatically reduce suicidal behaviors.)

Some quick thoughts on each of these and then we will dive deeper into the market size question. We plan to discuss the others in future posts:

Market demand has been vastly underestimated, we’ll examine that below.

There is now clear scientific traction. GLP-1s are showing strong efficacy in humans with a lot of room for improvement if designed specifically for addiction rather than for weight loss or metabolism. There are a number of other pathways that are showing promise as well, including orexin antagonism.

Trial cost is a tough challenge for any brain related disease, but the global market size for addiction should be enough to make it well worth it. Moreover, we believe there is a role for government to support drug development. We have offered policy proposals in previous posts that could encourage smart risk-taking by pharma companies so that the potential financial benefits would clearly outweigh the expense.

Reputational risk. The public and health regulators are smart enough to know that medications studied in unstable populations could have some complications in trials. The fear of blowback for deaths in an addiction study is overblown and in fact, companies will be widely cheered for pursuing more effective treatments. Solving addiction at scale would be a world-changing triumph.

The sales potential for addiction medicine has been dramatically underestimated

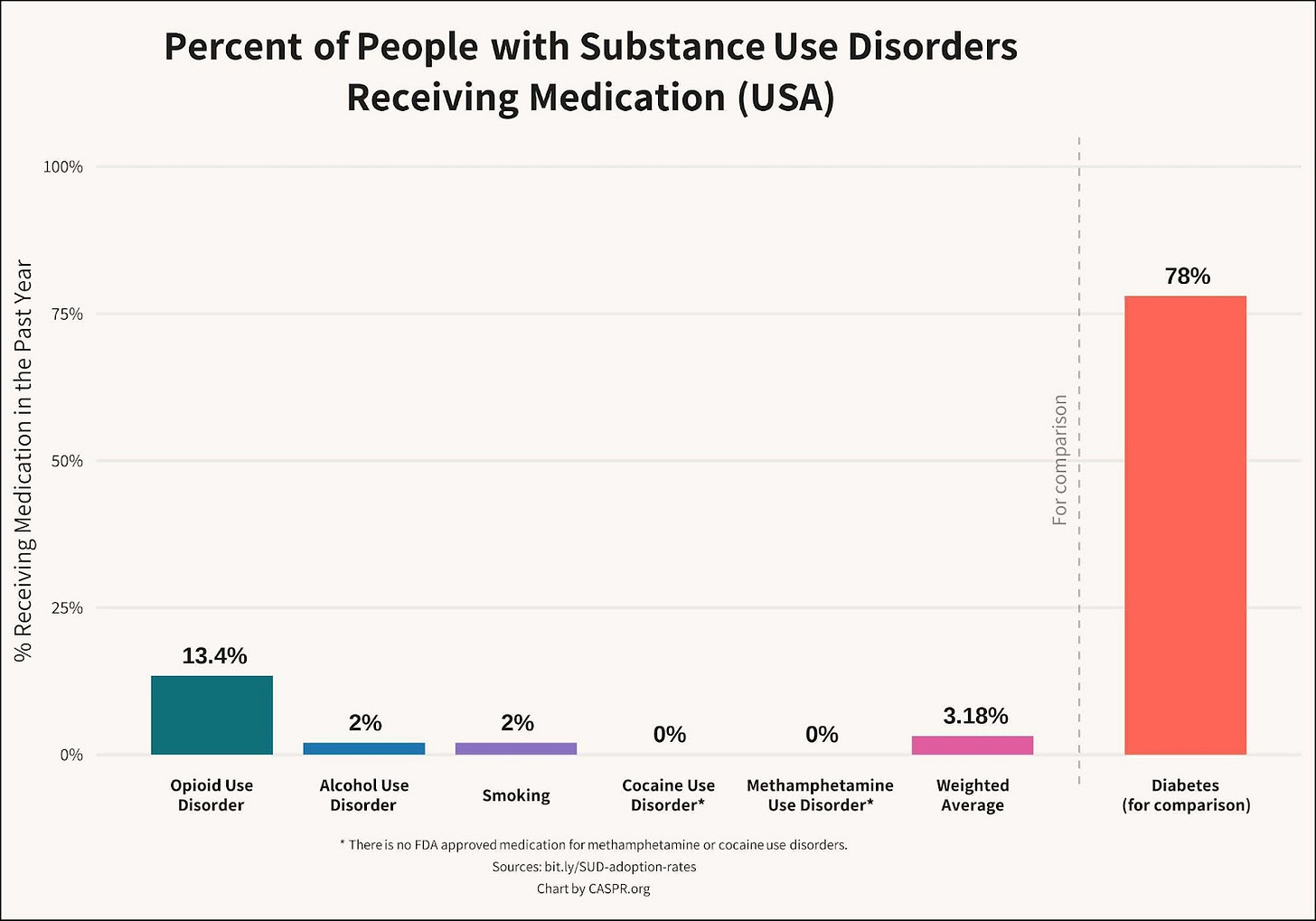

While tens of millions of Americans have substance use disorders, only 3% take medication:

At its root, the perception that addiction medication is a small market comes from assuming that the current state of addiction medication is a mature market with established dynamics. That’s far from the reality.

Some existing addiction medication is restricted, but novel medications won’t be

For opioid use disorder (OUD), the most effective medications are methadone and buprenorphine. These opioid-based therapies are effective when used consistently, but have struggled to reach more than about 13% of OUD patients because of decades of regulatory restrictions, side effects, a high burden for adherence, and limitations in efficacy. The FDA crackdown on opioid overprescribing has meant that doctors who prescribe opioids, even opioids for treating OUD, are monitored by the government and must take training courses. Jeffrey Singer at CATO, has argued convincingly that these burdens are limiting the number of providers who are willing to work with OUD patients.

However, novel medications for addiction that are not opioid based will not have these restrictions and will be much easier for non-specialized providers to offer and manage. One reason that addiction clinics are so important in current treatment is that the tools we have now require complex onboarding, often including managed detox and ongoing monitoring. Novel medications that require only weekly or monthly self-administration could drastically improve adherence rates.

Legacy therapies are substance specific, but this is not inherent to treating addiction

Existing therapies are focused on specific substances rather than broader substance craving. That means there is little overlap in medications for cigarettes, alcohol, and opioid addiction. (Naltrexone is one exception that is use across substances but due to limited efficacy and difficulty onboarding, it has not reached a large number of patients.)

If you are analyzing a potential drug strategy that is focused on a specific substance use disorder, you will be expecting a smaller market size. However, as GLP-1s have shown for food and substances, it is possible to broadly reduce craving. Medications that do so can be adopted by a much wider patient pool.

There is a false assumption that most people with substance use disorders do not want treatment

In addiction medicine, more than any other field, there is a perception that treatment refusal is at the root of the low rates of medication adoption. The belief is that most patients won’t take medication because they don’t want to stop using their drug of choice. This is false.

Particularly for opioid addiction, candidates for MOUD are typically highly informed or experienced regarding the side effects, difficulty of adherence, and high logistical burden of beginning buprenorphine or methadone– either they’ve tried these medications before or have close friends who have. If someone refuses to begin long-term methadone treatment, it tells us almost nothing about whether they would accept a more appealing option with less side effects and stigma.

While there are many people who will insist that they don’t want to reduce dependence on a substance, the vast majority of people with substance use disorder frequently express a desire to be free of that burden. Even among those who express resistance to treatment, many could be convinced by family and friends to accept treatment if productive and appealing options were available. This is especially true for long-acting therapies, dosed weekly or monthly.

The fact that some rehab centers are able to charge over $40,000 per month, while having mediocre efficacy, shows how many patients and families feel desperate due to a lack of palatable and long-term effective medication options.

The very small percentage of addiction patients currently taking medication makes the current addiction medication market appear small. But like so many disease areas that had low medication adoption rates until there was a breakthrough, addiction currently lacks appealing medications but has huge growth potential.

No one wanted weight loss drugs until they were great

The recent market growth for weight loss drugs is a useful comparison to the addiction market.

In 2012, before GLP-1 drugs arrived, global obesity medication sales were roughly $400M (best source I could find!). A study of prescribing from 2009 to 2015 showed just 1.3% of patients eligible for weight loss drugs filled at least one prescription. That’s half the rate for substance use disorders, which we’ve already seen is tiny. Here’s an article from 2016 about how badly weight loss drugs were selling.

Sales were bad because the medications on the market didn’t work well. The best medications at the time caused patients to lose about 5% of their weight and came with side effects. People who tried them stopped taking them and didn’t tell their friends to try them. Did those pitiful sales numbers indicate that people weren’t interested in medication to lose weight?

You already know the answer… with the arrival of Ozempic, efficacy more than tripled, to 15%-25% of body weight, and demand exploded.

Semaglutide and tirzepatide sold about $25B last year for obesity and diabetes, overlapping indications. They would have sold far more if Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk could produce them fast enough, but they are still in chronic shortage due to the incredible patient demand. Sales by 2030 are estimated to be over $100B as supply expands and even stronger GLP-1s arrive on the market.

The small size of the current addiction medicine market is entirely due to the limited efficacy, side effects, access obstacles, and adherence challenges of currently available medications. Addiction now is where weight loss was in 2015. If efficacy doubles or triples or adherence gets a lot easier, there will be the same explosion in sales that we’ve seen for weight loss medications.

Addiction is a huge opportunity for pharmaceutical companies

Some investors do see the immense potential in the addiction market. As Francisco Gimenez from 8VC told me:

Addiction is one of the largest diseases of unmet need in the USA. ~50mm Americans have had a substance use disorder in the past year. This is a chronic condition on par with obesity and depression with greater negative externalities to society. There is a stigma towards treating this issue like a disease which has hampered interest from the biopharma community, but if you look at it from first principles, it is one of the largest opportunities in history.

Addiction therapies present an extremely compelling, and wide-open opportunity:

The disease burden is huge

Addiction (which includes alcohol, nicotine, opioids, and stimulants) causes more deaths in the United States than any other disease, including cancer and heart disease. And many of the deaths from cancer and heart disease are actually downstream effects from smoking and drinking. Beyond deaths, addiction causes chronic disability and horrendous personal and community consequences. For example, 40% of violent crime is committed while drinking alcohol. The social and financial opportunities are immense.

Addiction is a chronic disease

People who are being successfully treated with a medication might remain on that medication for decades. While the public health dream would be a treatment that cures the addiction permanently, without any ongoing treatment, medication use will likely be long-term for most patients.

Addiction is under-competed

There are no major pharmaceutical companies actively pursuing addiction therapies. The most promising new medication class for addiction, GLP-1s, came out of metabolism research. So far Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and others are refusing to run studies on their GLP-1 drugs for an FDA indication for addiction. Any company that achieves this will have a huge market waiting for them.

We need drug companies who are brave enough to pursue an indications for addiction

I never thought I’d be writing an article cheerleading the pharmaceutical industry to develop new medications. But we need the private sector to reach people at scale.

Addiction medicine is underfunded by the US government and completely abandoned by big pharma. Over the past 20 years, if there had been private investment commensurate with the scale of the disease burden we would have already saved hundreds of thousands of lives. There is now clear scientific traction on reducing addictive drive. We need compounds developed specifically for addiction and we need companies that are willing to bring drugs through FDA approval for substance use disorders. This is an opportunity to restore people’s health and agency without turning ourselves into an authoritarian surveillance state. Doing so will be a world-changing achievement.

Do you work in pharma?

A number of our readers work for pharmaceutical companies of various sizes and I’d love to hear from you on how you see this challenge. Are there factors I haven’t considered here? Are things changing in the industry? Do you expect smaller pharmaceutical companies to seek indications for their own GLP-1s as a way to carve out a niche in the market? Please comment or write to me directly– we’ll be covering this topic on an ongoing basis.