FDA’s new National Priority Vouchers could grow the addiction medicine pipeline

Significant progress towards CASPR's goal to create a PRV for addiction medicine

CASPR works on both policy and research for next generation addiction medicine. It’s a tough time in addiction policy and medicine, as the big federal agencies, NIDA, NIAAA, and SAMHSA, are having their budgets slashed and research programs being cut across the country.

But there is some promising news from the FDA, and a policy win for our efforts to accelerate the development of new addiction medicines: the new National Priority Voucher (NPV) program. Based on statements from the administration about fentanyl and addiction, we expect that this program will include addiction medicine as a ‘national priority’ and could significantly accelerate the approval process for addiction drugs, potentially saving 10 months on drug approval timelines.

CASPR was the first organization to propose a priority review voucher for addiction medicines, we’ve met with dozens of Congressional offices to support a program, and Joe Lonsdale included our PRV recommendation in the influential ‘Make the FDA Great Again!’ paper. This new FDA effort delivers many (but not all) of the benefits that we believe can draw more companies into addiction medicine development.

Does 10 months faster matter?

In a disease area like addiction, which is profoundly lacking in late stage drug candidates and FDA approvals, speeding drug approval might seem pointless– getting nothing approved 10 months sooner is still nothing. But the potential to save 10 months on a drug development program matters tremendously to drug developers and investors who decide whether to launch a new medication program.

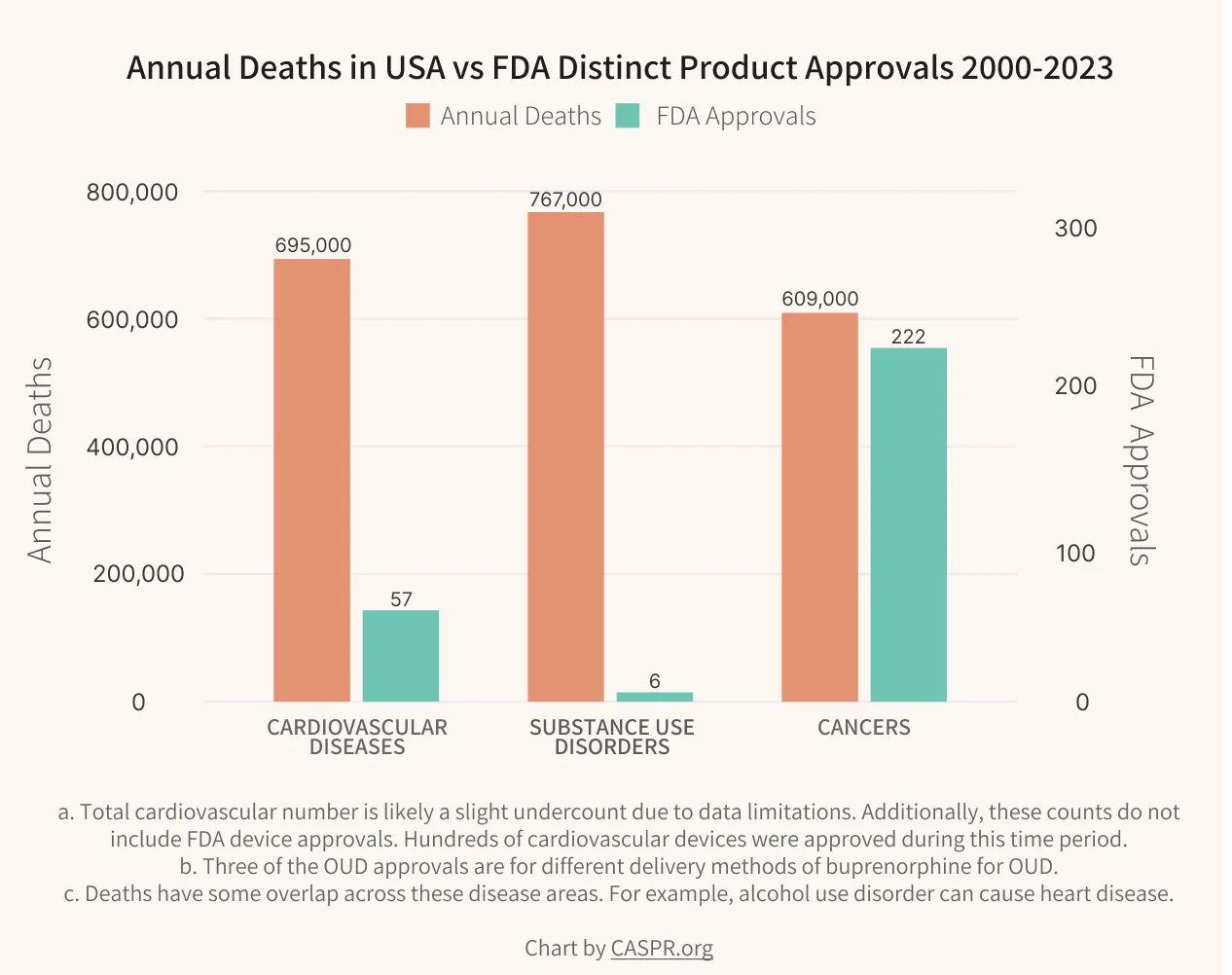

Despite a massive burden of disease, addiction medicine is currently a desert for innovation. The core thesis of our policy work is that this neglected disease area needs new incentives to jumpstart innovation. Last fall, CASPR published our Innovation Agenda for Addiction along with the Institute for Progress and with the Federation of American Scientists. It proposes actionable steps to accelerate breakthroughs in addiction medicine.

The Agenda introduced a novel proposal to expand the FDA’s Priority Review Voucher (PRV) program to incentivize medications targeting substance use disorders. The existing FDA PRV program has been very successful in spurring innovation in other neglected disease areas, and we believe it can work here as well.

Since publication, passage of a PRV has been our top policy goal and we have been actively engaging lawmakers and policymakers on the topic. This new National Priority Voucher is being created at the FDA without a new law being passed and, likely for this reason, does not go off the same benefits as the existing PRV programs, which allow resale of earned priority review vouchers. Selling these vouchers is a vital source of funding for biotechs working in neglected disease areas, as each voucher is worth over $100M. We will continue our work to advance legislation for a full addiction PRV program in Congress.

Still, the introduction of the NPV is a potentially huge step forward and is a recognition of the need to give special incentives to disease areas with high social externalities. Addictions cause tremendous harms within families, relationships, society, and the economy– it makes sense for the government to prioritize development of better treatments.

A backdrop of painful cuts

The overall political and policy strategy behind our Innovation Agenda for Addiction is to advance nonpartisan policies that can lead to medications that can reduce substance use disorder at a population scale. Families, doctors, and politicians on both sides of the aisle want better medicines for addiction, making this a policy path that can side-step the entrenched ‘drug war vs harm reduction’ debates that have lead to policy paralysis.

We count this NPV as a good step towards supporting innovation but it comes at a time when funding cuts are destroying addiction research programs at universities and research centers. This is counter-productive, both medically and fiscally: anything that slows down our ability to make progress against addiction is tremendously expensive to both the heart and purse of our country. New medicines begin with basic science– if we lose that, we could face many more decades of woefully insufficient medications for addiction.