Canadian and American overdose death rates have been converging rapidly

The gap between opioid overdose deaths in Canada and the US has shrunk from 65.4% in 2016 to 22.6% in 2023.

STAT News ran an article on June 27 titled, To get basic standard addiction treatment, Americans should move to Canada. The piece cites numbers that are incorrectly labeled, mistakes a study cohort for a citywide population, and claims that Canada has far lower opioid deaths than the US based on total deaths rather than per capita deaths.

The reality is that even a cursory look at the actual data shows us that Canada’s opioid crisis is nearly as bad as the United States and Canada’s overdose rate has worsened far more quickly than in the US over the past 10 years.

While the core argument of the STAT article is fine– the US should make it easier and less stigmatizing to get addiction medicine– the wildly distorted portrayal of Canadian treatment success implies that improving access to addiction medication in the US would make a big impact on the opioid crisis here. When claims like this turn into received wisdom, and they have already been repeated elsewhere, it dangerously distorts policy and funding priorities.

Here’s the STAT headline:

When you find the article on Google, there’s also a subheadline in the search results, “The U.S. should look to Canada as a model for providing addiction treatment and prevent deaths from opioid overdose.”

Comparing apples and orange trees (and calling them both bananas)

Here’s the key claim about Canada’s performance:

“A study in Vancouver, Canada, showed that up to 85% of people with opioid use disorder had access to addiction therapy, compared to only about 20% in the U.S.”

The first obvious problem is that one city in Canada is being compared to all of the USA, and I’ll get back to that in a minute.

The other problem is that the referenced 85% and 20% numbers are both mislabeled and are also measuring different things from one another. The “about 20%” number (which is actually 22%) comes from an estimate of the percentage of people in the US with opioid use disorder (OUD) who have received medication in the past year, not an estimate of ‘access to addiction therapy’:

Researchers found that in 2021, an estimated 2.5 million people aged 18 and older had opioid use disorder in the past year, yet only 36% of them received any substance use treatment, and only 22% received medications for opioid use disorder.

If 36% of people received treatment, a number from what is literally the same sentence, then it’s impossible that only 20% of people have ‘access to addiction therapy’. Even if you only care about access to medication, the percentage of people taking a medication is not a measure of how many people have access to a medication, just as the number of people who take Tylenol on a given day is not a measure of how many have access to Tylenol or how difficult it is to get.

Turning to the Vancouver study, the 85% number is neither a measure of the people with opioid use disorder in Vancouver with access to treatment nor the percent who received medication. It’s actually a measure of the number of people ‘linked to addiction care’ from a specific study population:

“Individuals are recruited through snowball sampling and extensive street outreach in the greater Vancouver region.”

This population is a narrow subset of people in Vancouver with OUD, a street-linked population that has been specifically targeted for outreach. It tells us nothing about overall treatment ‘access’ in Canada or the success of opioid policy in Vancouver. In fact, the reason that there is so much street-level treatment outreach to people with OUD in Vancouver is precisely because addiction and overdose death rates are so high in the city.

Canada has fewer people than America

The next sentence of the article is this: “Canada’s total number of opioid-related deaths are dwarfed by the same number in the U.S. because of how Canadians access therapy.”

Most of our readers know enough math to understand how absurd the beginning of this sentence is, but I’ll spell it out anyway: Canada has 40M people and the US has 335M people. If we want to understand the opioid deaths, we have to compare the rate per capita. Here is the opioid overdose death rate for each country:

USA - opioid overdose deaths per 100k in 2023: 24.2

Canada - opioid overdose deaths per 100k in 2023: 19.7

Canada’s rate is lower but not dramatically lower.

As glaring as this mistake is, the end of the sentence is more problematic: “because of how Canadians access therapy.” Since the referenced Vancouver study period in 2016, opioid overdose deaths in Canada have risen 184% while American opioid overdose deaths have risen by about 93%. Compared to the article’s statement, there would be more grounding to say: “Canadian opioid deaths have risen twice as fast because of how Canadians access therapy”, but of course that wouldn’t be based on any evidence of causality either.

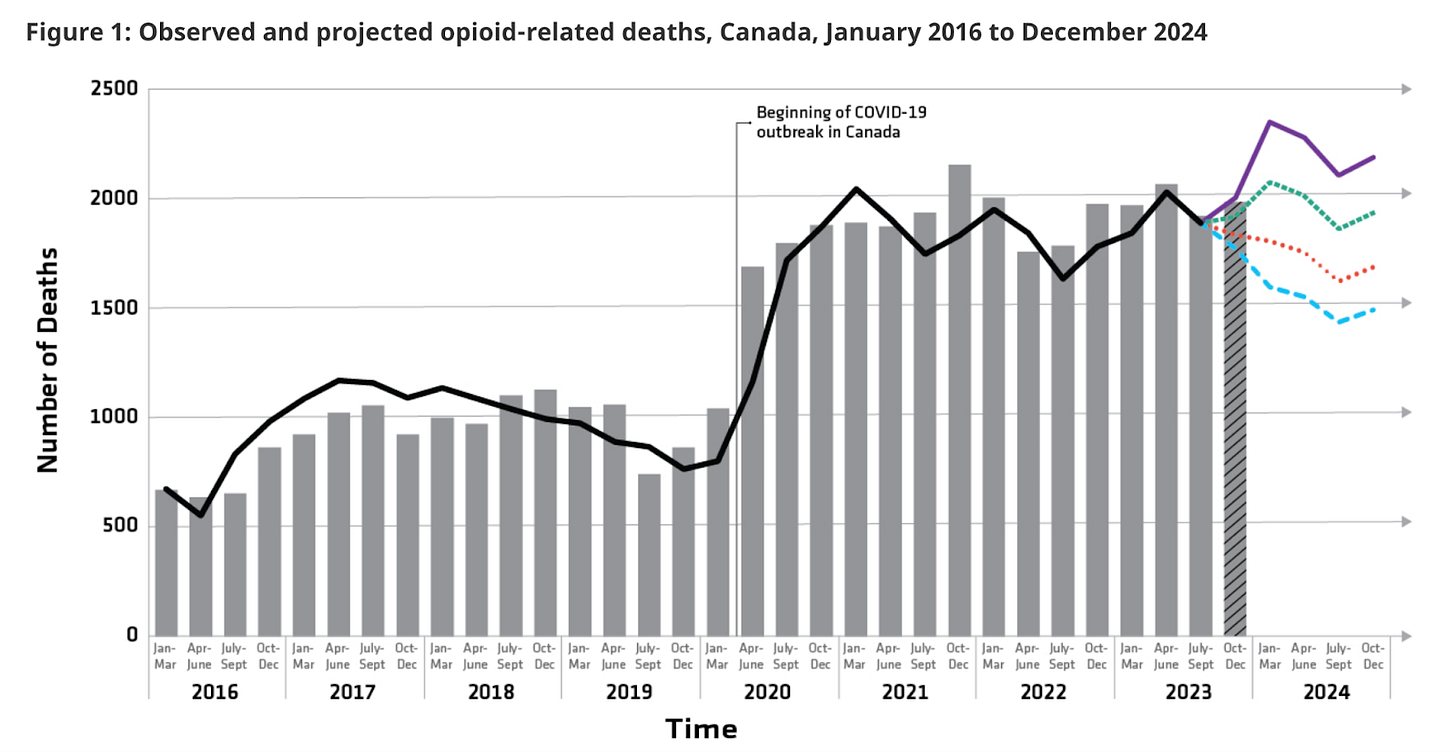

Here’s a chart of the massive increase in overdose deaths in Canada since 2016:

“To stop dying from overdoses, Vancouver residents should move to the USA”

If we are trying to compare the city of Vancouver to the USA, the British Columbia Coroner’s office shows that ‘Vancouver Coastal’, a health region that includes Vancouver, had 56.6 overdose deaths per 100k in 2023. That’s almost double the overdose death rate for the US, which was 32.6 per 100k in 2022 and the rate actually fell slightly in 2023. But of course, comparing a single opioid-embattled city to a whole country tells us almost nothing, which is why it shouldn’t have been done in the STAT article.

After I’d written a first draft of this post, The Economist happened to publish an excellent piece on Vancouver’s struggle with harm reduction and treatment for opioid use disorder.

Here’s their chart of the overdose disaster that has unfolded in British Columbia, where Vancouver is the largest city.

Compared to STAT, The Economist has a much more nuanced and informed assessment on how Vancouver and Canada are doing policy-wise:

Overwhelmed by fentanyl’s assault, the authorities have doubled down on ever further-reaching harm-reduction measures. Since 2020 medical professionals have been given licence to provide thousands of addicts with full-strength prescription opioids, free of charge, in the hope that this will keep them away from unpredictable street drugs. The pills are mostly hydromorphone, a commonly used painkiller, but some hard-core users insist on pharmaceutical fentanyl. Most controversially, BC last year became Canada’s only province to decriminalise the possession of small amounts of all drugs subject to abuse—methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin, fentanyl, the lot.

But deaths have been surging anyway, straining the case for harm reduction and posing political risks for Justin Trudeau, the prime minister, and other politicians who have supported it. It is still too early to declare the policy a failure—there are many factors behind the recent surge in overdose deaths, including the covid-19 pandemic, which left many drug users dangerously isolated. Reinvigorated harm-reduction policies have not yet been running long enough to generate sufficient data to offer clarity on whether they are working against fentanyl.

Why the STAT article matters

Does one op-ed in STAT really matter? It does because readers and other publications look to STAT as a reliable source for medical information. I didn’t come across the article when it was published, instead I read about it in ASAM Weekly, emailed last Tuesday to thousands of scientists and clinicians. It paraphrased the STAT article this way:

On the treatment side, studies show that up to 85% of Canadians with OUD have access to care. Compare that to the US, where our best numbers don’t even break the 20% mark (STAT News).

This is a serious problem.

ASAM, understandably, trusts STAT to get basic facts correct. They aren’t checking every link of every article and I wouldn’t expect them to. So then when ASAM, an association of doctors and scientists, paraphrases STAT, it makes this mess sound even more like it’s based in some kind of reality and then thousands of doctors, scientists, and policymakers internalize incorrect information. It would be easy to come away thinking that addiction treatment and overdose prevention is working well in Canada. We will be asking STAT to revise the article and headline.

Importantly, I do agree with the STAT author that the US should ease access to addiction medications, that Canada is better at providing medication access, and that the rate of addiction medication adoption and adherence in the USA (and Canada) is pitifully low. But general agreement doesn’t mean we can throw away any sense of scale or accuracy.

False narratives make it harder to develop evidence based policies. Telling Americans their neighbors in Canada are doing a far better job (85% vs 20%!) implies that a solution is at hand and it’s just political obstacles in the way. The reality is that we need radically new strategies for the public health emergency of fentanyl.

Addiction medication adoption has hit a wall

The STAT article is correct that we need more people with OUD receiving addiction medication treatment. But the distortions imply that access to the medication is the primary obstacle when in fact the larger obstacle is the lack of patient interest in using and continuing to use existing opioid addiction medications. This distinction has massive implications– if new policy efforts focus only on prioritizing access to existing MOUD rather than advancing new medications, the crisis will rage on in both the US and Canada.

In fact, I think the above referenced estimate that 22% of Americans with OUD receive addiction medication is too high. This more recent study finds that the number is 13.4%. I can’t find a similar study for Canada that estimates overall OUD medication rates, which would be the comparison that the article implied it was making. (Please get in touch if you do have a source for this— I can promise you it’s nowhere near 85%.)

We at CASPR have been making the case that the unpopularity of existing medications for addiction is due to the limited efficacy, adherence difficulties, side effects, and lack of patient interest. What we currently have to offer people with opioid addiction are unpopular and unappealing medications, even when made readily accessible and covered by insurance or Medicaid, or in the case of Canada, their national healthcare system.

Here’s a chart that our team made recently to illustrate just how low addiction medication adoption rates really are.

Are there lessons we can learn in comparing the US to Canada?

Looking at overall opioid overdose death rates in 2023, the US had about 22.6% more opioids overdoses per capita than Canada in 2023. That’s a meaningfully higher number, but not dramatically so. Is Canada’s moderately lower overdose death rate because of medication access? It’s possible. There are so many confounders of opioid prescribing history, fentanyl supply, and geography that we will probably never know for sure. Evidence generally points towards medication access being positive and Canada definitely does better at providing access. Expanded access is clearly not enough to solve the crisis or even stop it from worsening, but it probably does save some lives and the US should do a lot better.

But the more compelling question in my mind is this: why has the gap between Canada’s opioid overdose death rate and the US rate been shrinking so quickly since the mid-2010s?

Based on the numbers we could find, Canada jumped from 7.9 opioid overdose deaths per 100k in 2016 to 19.7 per 100k in 2023. And you can see in the above chart from the Economist that at least in British Columbia, there was already a big jump from 2014 to 2016. During the same time period, the US went from 13 opioid deaths per 100k in 2016 to 24.2 per 100k in 2023.

Comparing the two, the US opioid overdose death rate was 65.4% higher than Canada in 2016 but only 22.6% higher in 2023. Canada had far fewer overdoses than the US in the period before fentanyl began to dominate the opioid supply. As fentanyl grew, the gap between the US overdose death rate and the Canadian overdose death rate shrank. Why?

A theory: most of the science on opioid medication and treatment processes was developed through studies on heroin and prescription opioid users. Fentanyl is different– much stronger, more addictive, easily combinable with stimulants, and more difficult to reverse during an overdose. I suspect that fentanyl has steamrolled the policy, enforcement, and harm reduction efforts that were designed for a different era.

Perhaps pre-2015, Canada’s vastly more compassionate approach to drug treatment and easier access to addiction medication compared to the US made a big difference in reducing heroin and prescription opioid deaths. As fentanyl arrived, it reduced the effectiveness of the public health and treatment efforts that had been working better in Canada vs the US. When fentanyl takes over, harm reduction efficacy drops and deaths seem to rise until fentanyl penetration reaches its own natural equilibrium. This would explain a convergence in death rates.

The Economist piece seems to reach a similar conclusion,

Harm reduction alone can do no more than its name implies. It seems to be helping to reduce the body count, but by itself it cannot cure all the damage done by drugs as potent as fentanyl and other synthetics. “The drug supply is changing under our feet. It’s not like a mutating virus but a whole new disease,” says Bohdan Nosyk, an addiction researcher. The disease will need new treatments.

Are we ready to believe what the numbers are telling us?

Circling back to where we started, why did distorted statistics like these get published at STAT? I believe it comes from a deep frustration with how the USA has needlessly restricted life saving medications for OUD. This leads to motivated reasoning that will believe anything that supports a narrative that the US is failing in comparison to more compassionate countries, to the point that statistics which are implausible on their face are accepted without being checked.

Addiction medicine providers, researchers, and advocates have spent decades fighting to expand access to medications that reduce overdose rates. Progress has been made, but there’s a long way to go. And they are fighting against opponents who often use morality, shame, and incarceration as a substitute for science, medicine, and compassion. It’s understandable that this would lead to a strong desire to defend and expand access to the tools we have.

But we can’t let opponents of science make us so defensive that we stop caring about the evidence. That means we need to be honest about what works and what doesn’t. In this case that means being realistic about the inherent limitations of currently available medications for opioid addiction.

In 2022, the X-waiver was removed, making it easier for providers in the US to offer buprenorphine to patients. This was a huge victory in increasing access to opioid medication. But to almost everyone’s surprise, this loosening of restrictions did not increase prescriptions of buprenorphine.

More recently, the massive, well-designed, and well-run $349M HEALing Communities Study implemented a series of what have been understood as best practices for reducing opioid deaths. The study failed to impact opioid death rates in the communities where it was implemented compared to control communities. The field of addiction must take this failed result very seriously.

As the HEALing study demonstrates, there are serious limitations to our current tools, even when they are well deployed. We should continue to demand incremental improvements to access and implementation while also being realistic that we need dramatically better and more appealing medications that can impact the opioid crisis at population scale.

What can we do now?

There is both short and long-term hope for new treatment strategies due to recent medical breakthroughs in reducing addictive drive and developing non-opioid painkillers.

In the near-term, GLP-1RAs have shown significant reductions in alcohol consumption and opioid cravings in small randomized controlled trials and large retrospective studies. CASPR (that’s us) has published the most extensive strategic and scientific report on the promise of GLP-1RAs for addiction. These medications are extremely safe, already FDA approved for other conditions, and already in use by physicians off-label for alcohol and opioid addiction. They are also compatible in combination with existing medications for opioid use disorder and don’t require abstinence, which makes them compatible with harm reduction approaches. Most importantly, they are vastly more appealing than current medications and bring with them holistic physical and mental health benefits, giving them the potential to reach many times more patients than existing medications. That scale of reach is what’s needed to drive population level improvement.

Unfortunately, Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk have actively resisted calls to pursue an FDA indication for addiction, which would enable insurance coverage for patients, so it's left to the public to make it happen, either by forcing pharma to do so through legislation or, more likely, by funding and running the studies ourselves. Given this, NIDA and NIAAA should move aggressively to launch a range of short-term studies across different practice settings while also running large trials specifically designed to establish an FDA indication for opioid use disorder, alcohol use disorder, and cigarette smoking.

More broadly and simultaneously, Congress should dramatically increase medication development funding for NIDA and we should pressure and incentivize pharmaceutical companies to develop medications for addiction. Here’s what we’ve proposed for funding expansion.

In short, the US and Canada both desperately need treatment and public health approaches that will be embraced by a vastly larger percentage of the people affected by OUD. Everyone wants the same thing as the author of the STAT article– better and more widely adopted treatment for people affected by addiction. We won’t solve our crisis by copying Vancouver because their crisis has been worsening rapidly. But we can solve the opioid epidemic if we are honest about following the science and ambitious about doing what is needed.

For more, here’s our argument that we need to focus on strategies that scale.

Why should you subscribe to Recursive Adaptation?

We are focused on new policy strategies and breakthrough treatments. Enter your email below to subscribe, it’s totally free.