GLP-1 for Addiction: the Medical Evidence for Opioid, Nicotine, and Alcohol Use Disorder

GLP-1s like Ozempic and Mounjaro have the potential to reach far more patients than existing medications and permanently reduce addiction rates at a society-wide level.

Most recent update: February 24, 2025.

This article is regularly updated as new research studies are published. We believe this is the most comprehensive and up-to-date review available of the scientific evidence and policy opportunities for GLP-1RAs and addiction reduction. Subscribe below (it’s free) to be notified when new research is released.

The consistency that I'm hearing from all across patient groups is gain of control, whereas previously, there was a loss of control… All of a sudden they're able to step back and say, 'oh, well I had this shopping phenomenon that was going on, gambling, addiction, or alcoholism, and all of a sudden, it just stopped,'

- Dr. Gitanjali Srivastava, Vanderbilt Medical Center

Table of Contents

Part 1: Advantages of GLP-1RAs for Addiction

Part 2: Research Evidence

Part 3: Towards Broad Adoption

Introduction

Evidence that GLP-1 treatments like Ozempic and Mounjaro have strong anti-addictive effects across substances and behaviors has been mounting every month. This article reviews the published studies in the field, including two new randomized controlled trials in humans, as well as the strategic opportunity they present to reduce addiction at a society-wide level. The strength of the anti-addictive effect of GLP-1s appears so clear that many physicians are already using these treatments for patients with substance use disorders (SUD).

Addiction kills more Americans than cancer or heart disease but only 3% of people with substance use disorders currently receive medication— better treatments may be our only path out of the addiction crisis. With new research released since February, we are now at a point where the evidence for GLP-1s and addiction is stronger than it was for mRNA vaccines when Operation Warp Speed began, and there are far more lives at stake. The magnitude of this moment is hard to overestimate.

GLP-1s Create an Opportunity to Permanently Reduce Addiction, at Scale

Drug overdoses now cause more than twice as many annual deaths in the United States as HIV/AIDS caused at its peak in 1995 (109,000 vs 45,000). Overdose deaths are just one part of the mortality burden— addiction kills even more people slowly. US deaths from excess alcohol use are 178,000 per year and deaths from smoking are 480,000 per year. That’s a total of about 767,000 annual deaths from substance use disorders. For context, COVID deaths peaked at 450,000 annually and are now ~90% lower than peak.

Medications to address addiction only work if people take them. Existing addiction treatments face a number of obstacles to adoption that have severely limited their use, including patient resistance, stigma, side effects, low long-term adherence rates, and, for treatments like methadone, massive cultural resistance that has persisted for over 50 years, despite a mountain of evidence showing the public health benefits of expanded access. As we have seen so clearly in recent debates on vaccines and reproductive rights, it can be far easier to make sustainable progress in science and medicine than in culture and politics. Because GLP-1 drugs are not opioid-based treatments and are not primarily SUD treatments, they are positioned to completely bypass the culture wars surrounding substance use treatment, which will enable them to have a dramatic impact on the global prevalence of addiction, at a scale that existing treatments cannot reach.

We believe that if addiction is truly understood as a disease and a public health emergency, we have both a moral obligation and a strong self-interest as a society to move as quickly as possible to bring effective treatments to patients, at scale. If we can reduce opioid, stimulant, alcohol, and nicotine addiction by just 20%, we would avoid ~150,000 deaths per year and incalculable suffering for families and communities. But we believe even more is achievable. A 40% reduction in harmful addiction over 8 years can be accomplished with a coordinated strategic plan. We will be publishing specific strategy proposals over the coming months.

GLP-1RAs Are Uniquely Compelling for Addiction Treatment and Prevention

“I started prescribing it for this use about a year and a half ago, so far I've prescribed it to maybe a dozen patients just for this reason. Success so far seems to be much higher than naltrexone but I have a limited number of patients and time that I have turned that with comparatively.” - From a CASPR interview with an MD about semaglutide for AUD

If upcoming studies confirm existing data, GLP-1 drugs will be, by a wide margin, the most widely deployed anti-addiction medications. In fact, because of the scale of prescribing for obesity, far more people with alcohol use disorder (AUD) are already taking GLP-1s than existing indicated anti-addiction medications, as we examine below.

The magnitude of this potential comes not just from the large apparent effect size for addiction reduction, which may or may not exceed that of existing treatments, but from the possibility of reaching a scale of adoption that far exceeds legacy therapies. In short, GLP-1s present our first real opportunity to modify the arc of the opioid crisis and drive a major reduction in deaths from alcohol use disorder and tobacco.

Throughout medicine, but perhaps most critically in addiction care, the main predictor of treatment success is often the patient's motivation and ability to access and maintain long-term medication adherence. Addictive drugs and medications for drug use disorders exist in a complex matrix of economic and cultural constraints, regulations, logistics, and market dynamics. Evaluating the public health utility of a particular medication for OUD or AUD, for example, cannot happen without awareness of the societal pressures and institutional frameworks that surround patients and prescribers.

We must consider the full spectrum of patients’ culture, trauma, mental health, structural advantages and disadvantages, lifestyle, and economic resources when considering which medications can effectively address their addiction in a long-term, sustainable way that benefits overall health and restores agency. This is essential for patient success and a successful public health strategy. GLP-1s present unique opportunities to increase treatment rates while broadly improving patient health.

Reducing Addictive Drive and Preventing New Addictions

GLP-1s appear to reduce addictive behaviors across multiple substances and compulsive activities. These include alcohol, opioids, and nicotine (and, anecdotally, online gambling, skin-picking, excessive shopping, and other non-substance related compulsive behaviors). While the ‘addiction crisis’ is often focused on opioids and amphetamines, annual deaths from alcohol and cigarette smoking far exceed overdose deaths and AUD patients are even less likely than OUD patients to be treated with existing medications. Specific research is discussed below.

GLP-1s can prevent relapse in substance use disorder patients. Retrospective studies, detailed below, suggest that GLP-1s appear to both prevent addictions from occurring in patients taking them for diabetes or obesity, and to prevent relapse in patients with a history of substance use disorders. Additionally, by reducing cravings across substances, GLP-1s have the potential to reduce substance substitution by patients after a successful cessation.

GLP-1s may act as a “vaccine” for addiction, potentially leading to a significant public health impact, even without intentional use for addiction treatment. Because millions of people are already taking GLP-1s for health conditions like diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease, with more indications in progress, there are millions of people who will reduce their substance use simply as an unexpected, and maybe even unnoticed, side effect of the medications, as well as millions more who will avoid developing addictions or unhealthy substance use patterns in the first place. In this sense, GLP-1s may act as a type of ‘vaccine’ against addiction for some portion of the population. The rate at which GLP-1 use is growing means that this secondary effect could have a significant public health impact even without intentional use of GLP-1 for addiction treatment.

Additive to Existing Therapies

GLP-1s can be additive to existing anti-addiction treatments. There are no known contraindications of GLP-1 drugs with existing addiction treatments and GLP-1s work through a different mechanism of action than any existing addiction treatments. This means that treatments may be combined, with increased efficacy (as has already been seen in a small study, discussed below, that combined liraglutide with buprenorphine). It’s not hard to imagine a well-resourced family that is struggling with an opioid-addicted family member using a combination of GLP-1, Suboxone, and a contingency management service to achieve a very high probability of success and adherence.

GLP-1s may support progress towards reducing opioids in medical prescribing. By reducing cravings for opioids, GLP-1s may prove to be an essential tool for transitioning chronic pain patients onto non-opioid painkillers as they enter the market. This would be a huge step towards transitioning the medical system away from using opioids for chronic pain, which would reduce harmful side effects and prevent new addictions in patients and via diversion. GLP-1s also appear to reduce chronic pain in osteoarthritis and therefore may decrease demand for pain treatment.

Treatment Initiation and Compliance

GLP-1s do not trigger withdrawal or require detox. GLP-1 administration does not require patients to have cleared opioids from their system to initiate treatment for OUD and does not precipitate withdrawal when administered. For naltrexone and buprenorphine, two pillars of existing SUD therapy, the requirement to detox has been a major obstacle in treatment initiation. Initiation has become even more difficult in the fentanyl era. Withdrawal requirements also add tremendously to the expense of treatment initiation when they require in-patient treatment and housing to achieve.

GLP-1s are easy to get off. It’s much easier to convince someone to try a medication for addiction if they know that it will be easy to stop if they don’t like it or have an interruption in supply. GLP-1s can be stopped without taper.

GLP-1s may boost success rates for buprenorphine and naltrexone initiation. By serving as an immediate treatment option that reduces addictive drive without precipitating withdrawal symptoms, GLP-1 supported initiation onto buprenorphine and naltrexone may improve success rates by making it easier for patients to reach the short-term withdrawal thresholds required to begin treatment. We hope to see research studies on this specific question, as we have proposed below.

The dramatic and wide ranging health benefits of GLP-1s may increase SUD patient compliance. Over 70% of Americans are either overweight or have obesity, so a large percentage of the target population for addiction treatment already falls into the broad category of individuals for whom GLP-1s have well studied benefits for health and mortality. Physicians can currently prescribe GLP-1s off-label for addiction, or on-label for obesity or diabetes, while receiving the benefit of the secondary anti-addictive effect. This dual-purpose prescribing enables patients to receive insurance coverage for the on-label indication. Beyond these already indicated benefits, GLP-1s are being widely hailed for the additional health benefits that they appear to confer.

GLP-1 ease of use and weight loss benefits may improve long-term treatment compliance. GLP-1s are typically injected weekly and new compounds may eventually be injected on a monthly or even longer time frame. This makes them much better suited to treatment compliance than addiction therapies which require daily administration (and it should be noted that several longer acting formulations of existing SUD medications are coming to market as well). Additionally, the pro-vanity benefits of weight loss may function as a powerful adherence motivator for patients taking these drugs.

GLP-1s lack the stigma of addiction-specific treatments, and physicians are already familiar with prescribing them. Because GLP-1s are used primarily for non-addiction related diseases, and are used at such massive scale, they do not have the stigma that surrounds addiction-specific treatments. Stigma has been widely reported as a major obstacle for initiation onto existing treatments for SUD and for transitioning long term pain patients from oxycodone to buprenorphine. Additionally, physicians who lack experience or are uncomfortable prescribing SUD treatments will already have extensive experience prescribing GLP-1s. “These medications are becoming increasingly normalized, and very quickly. We know that many physicians will be comfortable prescribing them,” said Christian Hendershot, PhD, JAMA April 2024.

Positive Side Effect Profile

The side effect profile of GLP-1s is very favorable. The most common negative side effects of GLP-1 medications are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The gastrointestinal side effects often subside as patients acclimate to the treatment but do lead to treatment discontinuation for some patients. GLP-1s are also contraindicated for pregnancy and a few rare conditions. Because of semaglutide and tirzepatide shortages, which have forced patients to involuntarily stop and restart treatment, reliable data on adherence for GLP-1s is not yet available. Some providers have reported very high adherence compared to other medicines while other sources have reported more typical adherence rates. Overall, however, GLP-1s appear to have a wide range of positive side effects that were not expected or intended when the medications were developed, as is discussed at length below. Long-term opioid use, including methadone maintenance therapy (MMT), can have significant side effects, including dependence, cognitive impairment, and others. Buprenorphine, also an opioid, also has a significant long-term side effect profile, including over 60% of patients reporting sleep disturbances that may interfere with treatment. If GLP-1s can help reduce the effective dose levels for these vital treatments, that may be broadly beneficial for the health of patients. Naltrexone has a more positive safety profile but faces significant obstacles in treatment initiation for OUD.

Whole Patient Benefits

GLP-1s can address psychological factors, offer holistic benefits, and potentially reduce relapse triggers. Addictions are vastly more likely to occur in patients with trauma, anxiety, depression, and other mental health conditions. To most effectively treat these patients and prevent relapse, multiple psychological factors should be addressed. GLP-1s show broad mental health benefits in studies, including reductions in depression, anxiety, and neuroinflamation, as discussed below. Improvements in these domains mean that GLP-1s may provide holistic mental support that enables patients to enter a positive spiral of life changes and reduce factors that can trigger relapse.

Potential suicide reductions. GLP-1s appear to have a strong effect in reducing suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, as discussed below, both of which are common among SUD patients. We hope that retrospective studies on overdose rates among GLP-1 treated populations will follow.

GLP-1 mortality reductions in diabetes and obesity patients suggest overall health benefits. There are dramatic mortality reductions being shown for populations that are already taking these drugs for diabetes and obesity. When looking at the ‘whole patient’ and potential comorbidities, treatment with GLP-1s may be strongly beneficial for the overall health of many people with substance use challenges, both because of direct benefits as well as the potential to reduce the number of medications that patients require.

Access and Scale

Existing widespread use of GLP-1s by physicians across medical contexts creates an opportunity to reach the scale that will be required to substantially impact society-wide addiction rates. From a public health perspective, if we are working to end the opioid crisis and reduce rates of smoking and excess alcohol consumption, we need treatments that can scale to reach a large portion of the affected population. GLP-1s are uniquely positioned to achieve that scale because they are already used by physicians in so many contexts and have millions of existing patients. As a provider, if you can prescribe a single, once-a-week treatment that improves a patient’s metabolism, mental health, heart health, and blood pressure while reducing addictive drive and mortality, that is an extremely appealing option with high adherence potential. GLP-1s were named Science’s Breakthrough of the Year for 2023 because of the broad health benefits across disease conditions and the drugs are rapidly improving with each new generation. The number of patients on these medications is expected to continue rising quickly.

GLP1-s are already FDA approved. GLP-1s are years ahead of any other potential breakthrough therapies for addiction treatment in the pipeline (with the partial exception of the new Vertex non-addictive painkiller, suzetrigine). Many GLP-1s are already FDA approved and physicians can legally prescribe them off-label for any use. If our goal is to truly conquer addiction at a society wide level, this is a massive head start.

GLP-1s are non-opioid therapies. This means that they will not face the opposition or stigma that has severely limited access to methadone, despite clear medical and public health evidence of benefits from easing prescribing restrictions. Buprenorphine is more widely accepted than methadone but also faces significant ongoing stigma and has had difficulty scaling usage even as prescribing restrictions are lifted.

GLP-1s can help broadly destigmatize addiction and medications for addiction. In many ways, the current public discourse on addiction mirrors the conversation around obesity 4 years ago, before Ozempic burst onto the scene as a weight loss drug. Debates about agency, personal responsibility, body shaming, and ultra-processed foods dominated. Then suddenly, with the rise of Ozempic, patients started describing the disappearance of “food noise” (food-related mental chatter and distraction) and how their hunger dial had suddenly turned way down. The remarkable quotes from Oprah in this article capture the power that GLP-1s have to crisply reveal to patients, and the public at large, that obesity has a core biological component. The destigmatization that is well underway for food related drive could happen just as rapidly with substance addiction. For example, “booze noise” could someday replace “addict” in the self-conception of patients with AUD.

In short, the potential of GLP-1s to transform addiction treatment and overall addiction levels in society is massive. There has never been an addiction therapy that has shown potential on so many different dimensions that influence therapeutic and public health success.

Now we will examine the growing evidence of anti-addictive properties and mental health benefits of GLP-1s.

Surveys and Reports from Providers and Patients

Several human studies of GLP-1s for addiction, detailed below, have been initiated following widespread reports from patients and providers of unexpected anti-addictive effects from semaglutide and tirzepatide. At a high level, what appears to be most tangible about the experience of patients on GLP-1s is an abrupt reduction in cravings and compulsive behaviors and a sense of increased agency: the ability to make conscious decisions about what to consume, whether it is food or other substances, rather than feeling pulled by a strong internal urge. If anecdotal evidence feels like a distraction to you, feel free to skip this section and jump to the research studies. That being said, we do believe that patient narratives provide important clues about the rapid onset of effect and magnitude of effect size across behaviors.

While not a scientific publication, Morgan Stanley recently surveyed 300 GLP-1 users and found that alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking had dropped substantially. As reported by CNBC,

“Notably, the survey also found that 40% of participants reported smoking traditional cigarettes at least weekly before starting a GLP-1, but that number declined to 24% after treatment. Weekly e-cigarette use similarly fell from 30% to 16% of respondents.”

That’s a 40% decrease in cigarette smoking rates as an incidental side effect of a GLP-1. The same survey reported that about 60% of GLP-1 users reported drinking less alcohol since beginning treatment, with 14-18% quitting drinking completely. Morgan Stanley is warning investors that the alcohol companies Molson Coors, Boston Beer Company, Constellation Brands, and Diageo are most at risk of a significant sales decline due to the projected ongoing increase in GLP-1 users.

Here’s one patient’s narrative:

“I (37F) have been a pretty severe alcoholic for a decade or more. The longest I went without drinking in 10 years was 2 weeks. I would drink to blackout maybe 3 nights a week, sometimes more.. 7 to 10 shots of 90 proof vodka. Or more. My tolerance was pretty high. I titrated up to .5 semaglutide this past Friday and haven't had a drink or even a desire to drink since. I caught sight of the vodka bottle under my bed and started gagging… And I have tried medically assisted ways to quit alcohol which never worked. Yes there is such thing as booze chatter for me, and I no longer have it.” - Semaglutide patient

It is important to distinguish these reports from a typical placebo effect. When patients report a dramatic reduction in opioid cravings from a drug that was prescribed for a different condition (diabetes or obesity), it is unlikely to be a placebo effect because the reduction in cravings was not the goal or an expected impact of the treatment. In addition, patients frequently report that the reductions in substance use cravings occur immediately when they increase their dose and sometimes report that cravings return weekly as they reach day 5 or 6 before taking their next injection on day 7. Furthermore, patients report that substance cravings fully return with cessation of treatment and disappear again when treatment is resumed.

Beginning with Ozempic, and now reported even more strongly from patients taking Mounjaro and Zepbound, the sudden reduction of cravings that occurs at initiation or dose increase is perhaps best compared to the accidental discovery of Viagra. First developed for hypertension, patients in clinical trials for Viagra kept reporting that something… ‘interesting’ was happening when they took the drug. This was a specific and unexpected side effect, reported by a large percentage of patients, and, again, less likely to be a placebo effect. What we’re hearing from GLP-1 patients today is similarly specific, widespread, and unexpected. You can read our compilation of patient reports here and these are a few more representative examples:

“My pretty problematic drinking has reduced to very little comparatively. If my husband didn’t drink I probably wouldn’t at all… I’ll drink half a glass and then literally Saran Wrap it and put in the fridge. Compare this to being a nightly bottle of wine-plus drinker before… And this effect happened IMMEDIATELY.” - Semaglutide patient

Patient reports like these don’t just come from people with problematic substance use. Many people simply lose all desire for the occasional cigarette or beer with friends.

“I love drinking. I absolutely do. There's nothing better to me than a summer night outside listening to some live music with your friends enjoying a few beverages. But I just can't anymore. It doesn't make me physically ill at all, my brain just says, "Nope, you're done." I can't even explain it because I want to drink but I'm just completely done after one or two. It's kind of annoying if I'm being honest but I definitely wouldn't go backwards” - Mounjaro patient

“Loving this! My mom started when I did and used to have a drink every night. When I told her about the studies being done into alcohol she realized she hadn’t had a drink in over a week and had no desire for one. She’s not an alcoholic but she just liked having her nightly drink.” - Semaglutide patient

The reduction in desire and compulsion often goes beyond substances to include behaviors.

“I had a REALLY BAD impulse shopping problem. It went away totally when I started Wegovy. It was nuts I could not believe it.” - Wegovy patient

This CNN article has a story that really articulates the immediacy and unexpected nature of the positive impact for many:

A smoker for most of her life, Ferguson started Ozempic 11 weeks ago to try to lose about 50 pounds she’d gained during the Covid-19 pandemic, which had made her prediabetic.

She’d switched from cigarettes to vaping last summer in hopes of quitting but found vapes to be even more addictive. That changed, she said, once she started Ozempic.

“It’s like someone’s just come along and switched the light on, and you can see the room for what it is,” Ferguson said. “And all of these vapes and cigarettes that you’ve had over the years, they don’t look attractive anymore. It’s very, very strange. Very strange.”

Human Studies on GLP-1 and Addiction

A number of retrospective and pilot RCT trials on GLP-1s and substance use have been published or announced, with many more on the way.

Randomized Controlled Trial of Semaglutide for Alcohol Use Disorder

In a randomized controlled Phase 2 trial of semaglutide for alcohol use disorder (AUD), Christian Hendershot at UNC / USC found significant reductions in drinking among people taking semaglutide, particularly in reducing heavy drinking days. The effect size for reducing heavy drinking is far larger than what has been shown for oral or injectable naltrexone (Vivitrol). These results are in-line with provider reports that even those GLP-1 patients who do not become fully abstinent, reduce their heavy drinking and total number of drinks per week dramatically.

Previously: First-ever randomized trial of Ozempic for alcohol use disorder shows significant reductions in drinking

Randomized Controlled Trial for Liraglutide and Opioid Use Disorder

New results for opioid use disorder were recently presented at the American Association for the Advancement of Science conference by Penn researchers. In a small, randomized controlled trial, liraglutide significantly reduced opioid cravings among 20 patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). Over the three-week study, patients on liraglutide experienced a 40% reduction in opioid cravings, with this effect evident even at the lowest dose. Liraglutide is a previous generation GLP-1 and future studies will use more powerful current generation therapies like semaglutide or tirzepatide.

Liraglutide treatment appeared to be synergistic with buprenorphine, as reported by STAT:

Among patients already on buprenorphine, a medication approved by the FDA to treat opioid use disorder, those also on liraglutide were more likely to report zero cravings than the placebo group. This effect became statistically significant from the tenth day of the study onward, as patients were titrated to increasingly higher doses of liraglutide. “It suggests there’s an additive effect of these two medications,” said Andrew Saxon, an addiction psychiatrist at the University of Washington who was not involved with this study, potentially because liraglutide and buprenorphine target different mechanisms.

The stronger impact observed at the moment of dose escalation is consistent with patient reports that cravings for alcohol or opioids often disappear completely soon after a dose increase. But even low doses appear to have a positive impact on opioid craving reduction, which is promising for managing potential side effects like nausea or excess weight loss. In a recent interview, Patricia Grigson, one of the lead investigators, said:

“The GLP-1 drugs reduced craving beginning with the lowest dose of liraglutide, even when patients were reporting high levels of stress. Those on placebo usually experienced an increase in craving in the afternoon or evening. Our data showed that craving among those who were on liraglutide stayed flat.”

Dr. Grigson’s comment here about stress is particularly intriguing— so much of the conversation around addiction centers on the co-occurrence and precipitators of psychological stress, anxiety, and depression. GLP-1s’ ability to rapidly remove cravings may help disentangle some of the assumptions that these psychological factors necessarily must move in concert, just as previous research on addiction has found that ‘liking’ and ‘wanting’ a drug do not always co-occur.

The other principal investigator on the study, Scott Bunce, said, “Patients have told me that it slows down their need for immediate gratification of their craving, allowing them to make better — and healthier — decisions.”

The same research team is now planning a 200 person trial with semaglutide. According to Grigson,

“Because our preliminary data suggested that patients did better in the study if they were on both the GLP-1 drug and medication for opioid use disorder, in this study, half of the participants will be on methadone and half will be on buprenorphine for opioid use disorder treatment.”

Because semaglutide is stronger, is dosed weekly instead of daily, and has fewer gastrointestinal side effects than liraglutide, it may be even more effective in reducing craving while increasing real-world treatment adherence.

Semaglutide and Opioid Use Disorder

Dr. Rong Xu at Case Western and Dr. Nora Volkow, who runs the National Institute of Drug Abuse, published a paper in JAMA Network Open showing large reductions in the likelihood of opioid overdose among patients receiving semaglutide (Ozempic) for diabetes compared to other diabetes medications.

This study looked at patient health records for 33,006 patients who had opioid use disorder (OUD) as well as type 2 diabetes (T2D). It found that patients receiving Ozempic vs. other diabetes medications had between a 32% to 68% lower risk of opioid overdose, compared to other treatments.

Specifically, OUD patients receiving Ozempic have a 54% lower risk of opioid overdose than those taking metformin, a 58% lower risk than insulin alone, a 63% lower risk compared to DPP-4i, and a 42% low risk compared to SGLT2i.

Semaglutide and Alcohol Use Disorder

Rong Xu and Nora Volkow also recently published this new study of patient health records in Nature Communications that shows a 50-56% decrease in the risk of new or recurring alcohol addictions among people taking semaglutide.

These are dramatic results, consistent with other GLP-1 findings. The reduction in risk for new AUD diagnoses highlights the preventative effect that GLP-1s are able to provide.

This is a retrospective study and not a randomized controlled trial, so there may be confounding factors affecting which patients were given GLP-1 prescriptions rather than other treatments, despite trial controls. Compellingly, the reductions were consistent throughout the breakdown groups within the study and for both diabetes and obesity patients, all of which were examined separately. In addition, bariatric surgery, with a presumably similar patient intent, is associated with a small increase in AUD rates rather than the huge decreases seen here.

Another retrospective study shows that semaglutide is associated with a greater reduction in alcohol hospitalization (36%) than currently approved medications for AUD and is also associated with fewer somatic hospitalizations.

Semaglutide and Cannabis Use Disorder

The same team also published this study on semaglutide and cannabis use disorder (CUD) in Molecular Psychiatry based on patient health records. It shows 30-50% decreases in new and recurrent CUD in patients with diabetes or obesity who were treated with semaglutide vs non-GLP-1 medications.

Here’s a chart our team at CASPR created for the obesity results from this study:

Patients treated with semaglutide (Ozempic / Wegovy) showed a large reduction in the likelihood of new or recurrent cannabis use disorder (CUD) diagnoses compared to patients treated with non GLP-1 anti-obesity or anti-diabetes medications.

The same research team has already completed and submitted similar papers looking at the impact of semaglutide on treatment for opioid use disorders and smoking. When published, these papers will be extremely influential in the field of addiction. Nora Volkow’s participation in these studies hints at the impact to come.

GLP-1RAs Reduce Opioid Overdose and Alcohol Intoxication

A large retrospective study of patient health records for Loyola University Chicago shows a 40% drop in opioid overdoses and a 50% drop in alcohol intoxication among people who received GLP-1RAs (typically for diabetes or obesity).

The paper shows much lower rates of these negative incidents in the first month after GLP-1 prescribing:

Yet, notwithstanding this gradual decline in those not prescribed, rates of overdose and intoxication among those prescribed were immediately low even in the first month following index encounter and remained lower throughout the study period.

…

The index encounter was defined as the first instance of a GIP/GLP-1 RA prescription or a randomly selected encounter for patients without such prescriptions, both occurring after a first diagnosis date of OUD or AUD.

Notably, this study included broad range of GLP-1 drugs, including much older GLP-1s that have far lower anti-obesity, anti-craving, and anti-addictive effects:

abiglutide (Eperzan, Tanzeum), dulaglutide (Trulicity), exenatide (Byetta, Bydureon), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), lixisenatide (Adlyxin, Lyxumia), semaglutide (Ozempic, Rybelsus, Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro)

It’s possible that the associations that were found would be even stronger if the study had looked exclusively at semaglutide and tirzepatide, which are the current best-in-class options for weight loss.

Semaglutide and Tirzepatide for Alcohol Use Disorder

This study looked at real-world alcohol consumption behavior among individuals taking semaglutide or tirzepatide, and found dramatic reductions. From Semaglutide and Tirzepatide reduce alcohol consumption in individuals with obesity:

“In the remote study, we observe a significantly lower self-reported intake of alcohol, drinks per drinking episode, binge drinking odds, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) scores, and stimulating, and sedative effects in the Semaglutide or Tirzepatide group when compared to prior to starting medication timepoint (within-subjects) and the control group (between-subjects). In summary, we provide initial real-world evidence of reduced alcohol consumption in people with obesity taking Semaglutide or Tirzepatide medications, suggesting potential efficacy for treatment in AUD comorbid with obesity.”

Note: Beyond what is publicly available today, several studies from established research groups showing substantial anti-addictive effects have been submitted to journals and will be published in mid-2024. We will update this article as new research is published so it can serve as a resource to clinicians and policymakers.

Semaglutide and Exenatide for Smoking Cessation

Dr. Luba Yammine has shown efficacy for exenatide, an older generation GLP-1RA for smoking cessation, and she is currently running a Phase 2 trial of semaglutide that will track smoking cessation rates.

A patient health record study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine found dramatic reductions in prescriptions of smoking cessation medication for people taking semaglutide (Ozempic) compared to other diabetes medications. The study population was diabetes patients with existing tobacco use disorder (TUD). Compared to insulin alone, diabetes patients who began taking semaglutide were then 68% less likely to later receive a prescription for a smoking cessation medication. The study also showed significant reductions compared to other diabetes medications, including older generation GLP-1RAs.

Another real-world retrospective cohort study using electronic health records from TriNetX shows a 28% reduction in nicotine use disorder for patients taking semaglutide (Ozempic) vs other diabetes medications.

The same study also showed significant reductions in cognitive deficit and dementia risk.

GLP-1 Addiction Reduction Evidence in Rodents and Primates

Randomized controlled trials in mice, rats, and monkeys have shown strong anti-addiction effects from GLP-1RAs. Studies like these may eventually elucidate the mechanism of action for GLP-1 addiction reduction, which is not yet clear.

An early GLP-1 drug, Exendin-4, was found to reduce conditioned place preference and dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens in response to nicotine, cocaine, and amphetamine (a brain region that is understood to play a crucial role in the body’s reward system) as well as to reduce cocaine self-administration and seeking behavior in rats. Exendin-4 has also been shown to reduce response to addictive drugs such as cocaine, heroin, alcohol, and oxycodone. Exenatide, the human version of Exendin-4, has a short half-life and has not shown efficacy in human trials for addiction. Exenatide market share has shrunk rapidly since 2019 as longer lasting and more effective GLP-1s like semaglutide and tirzepatide have arrived, and with them, reports of anti-addictive effects.

Liraglutide, also a previous generation GLP-1, has been shown to reduce voluntary alcohol consumption in monkeys. There is also animal evidence to suggest that these medications may be able to intervene in precipitators of relapse— drug-associated cues, stress, and exposure to the drug itself. Additionally, liraglutide has been shown to reduce drug taking during self-administration sessions and drug-seeking following abstinence in rats and reduce cue-induced heroin seeking.

Semaglutide has been shown to dramatically reduce voluntary alcohol intake and prevent relapse-like drinking behaviors in rats and mice:

Positive and Holistic Mental Health Impacts of GLP-1s

“I cannot even begin to describe the relief I have felt from depression, anxiety, intrusive thoughts, and impulsive behaviors that I have struggled with my whole life, like skin picking and biting the insides of my mouth. This, above all the other things the medication has helped with, has improved my quality of life significantly.” -Zepbound Patient

“My anxiety has dropped to near nonexistent levels. I would like to stay on this medication forever at whatever dose keeps my anxiety at bay. I feel like a normal person for the first time in my life.” -Semaglutide patient

Remarkably, evidence is mounting that GLP-1 drugs may improve a wide range of mental health factors for patients, in addition to the anti-addictive effects discussed above. Improvements in anxiety, depression, and a reductions in suicidal ideation and suicide attempts appear substantial.

These holistic mental health benefits could greatly increase success rates for substance use disorder populations, beyond simply reducing cravings. Reductions in anxiety and depression may enable patients to make life changes that improve their environment. A reduction in suicidality could have substantial impact on intentional and semi-intentional overdose deaths, even among those who continue to use opioids at some level. Additionally, the combined effects of reducing cravings across substances and improving mental health may reduce the likelihood that a new substance will be substituted after cessation of dependence.

Anxiety and Depression Reduction

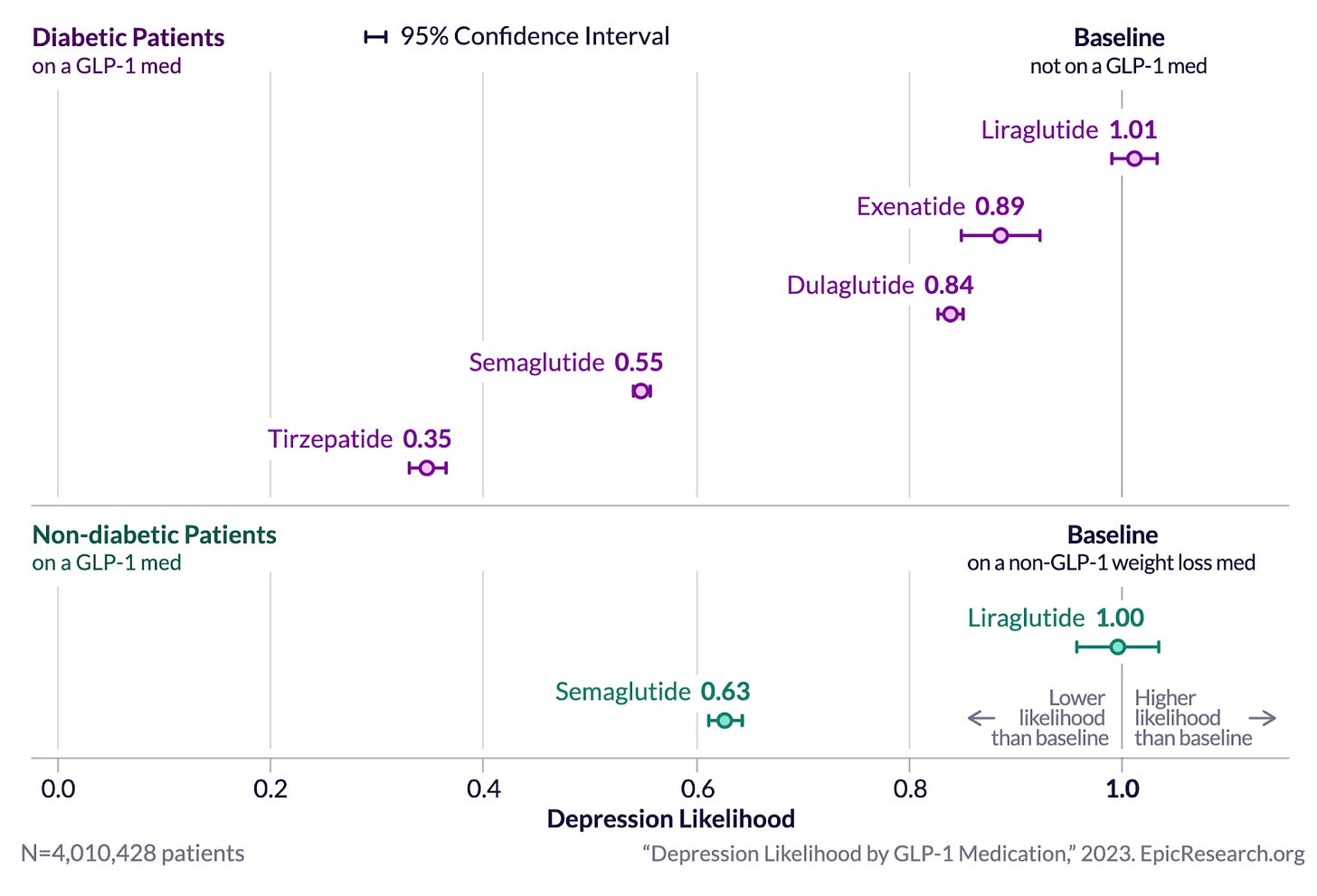

Epic Research published a remarkable patient health data analysis based on their Cosmos system which contains “233 million patient records from 1,325 hospitals and more than 28,900 clinics''. They found dramatically lower depression and anxiety scores for patients treated with GLP-1s. Crucially, the level of improvement was highest for the newest GLP-1 drugs, with tirzepatide performing best of all, consistent with Mounjaro and Zepbound patient reports.

Results for anxiety were similar:

Are these potential effects on anxiety and depression caused by the weight loss from GLP-1s? Patient reports indicate that the reductions in anxiety and depression, like the anti-craving effects, occur rapidly after initiation or dose increase and are not secondary to weight loss. That being said, over 70% of Americans are overweight or have obesity, so even if anxiety and depression reductions are driven by weight loss and don’t occur in lower weight individuals, a majority of the population may still see benefits in mental health. Additionally, this study on bariatric surgery shows a decrease in depression when people lose weight post-surgery but not a decrease in anxiety. This may suggest that the reductions seen from GLP-1s in both depression and anxiety are a direct effect, not subsequent to weight loss.

Reduced Suicide Risk

Multiple studies suggest that GLP-1s dramatically reduce the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

Published in Nature Medicine, this study found a 73% lower risk of suicidal ideation in patients with obesity or diabetes treated with semaglutide compared to those treated with other diabetes or obesity medications. Large risk reductions persisted 3 years later.

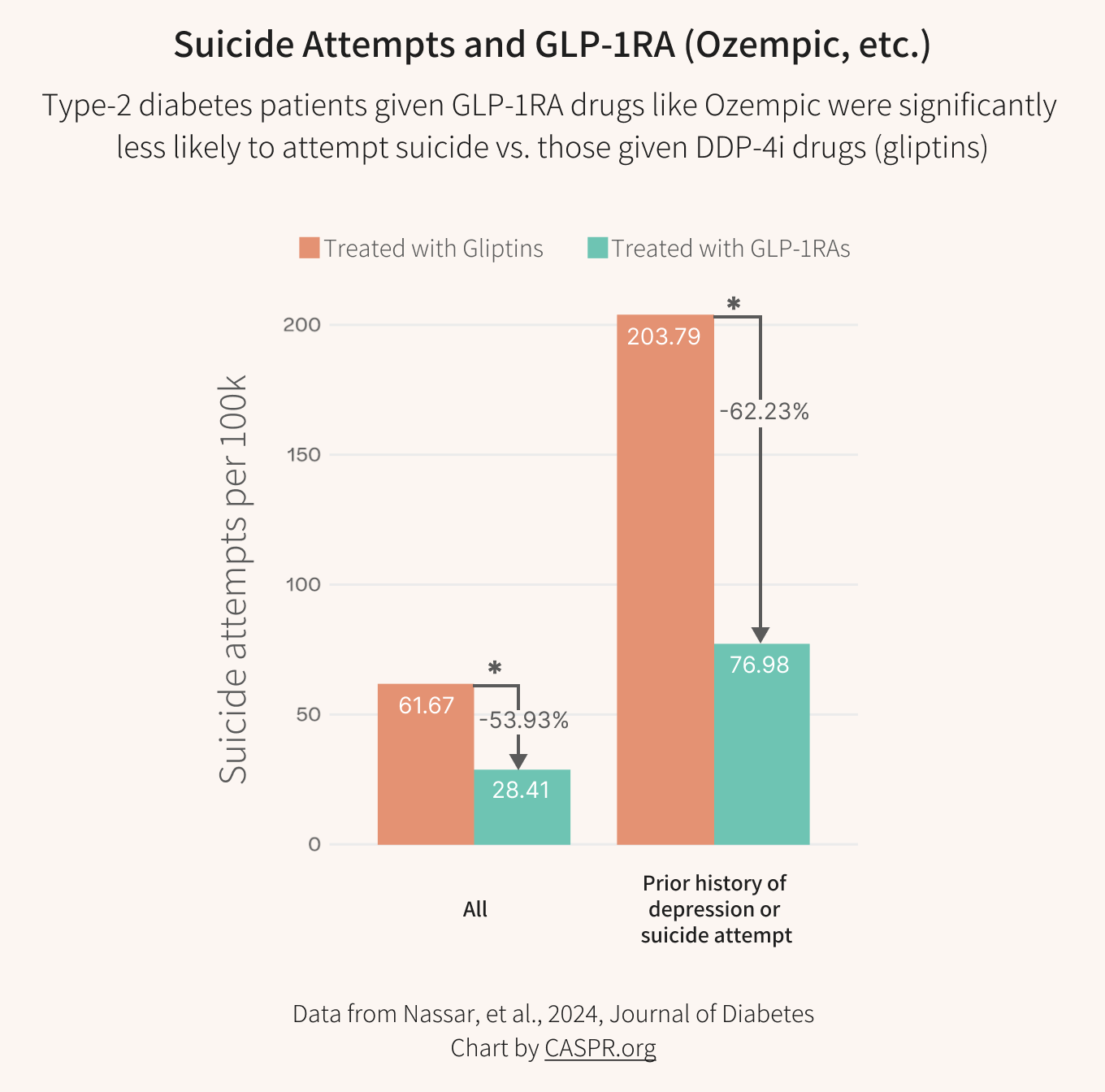

Another retrospective study looked directly at suicide attempt rates and also found a strong protective effect for people treated with GLP-1s. Here’s our chart of the results:

People with T2D treated with GLP-1RA consistently exhibited a lower risk of suicide attempts compared to those treated with DPP-4i. This was particularly significant in people with a history of depression or suicide attempts. The risk and odds ratios were significantly lower in the GLP-1RA-treated cohorts than in DPP-4i across all analyses.

The rate of suicide attempts was over 53% lower in the GLP-1 group and over 62% lower for people with a prior history of depression or suicide attempts. If supported in further studies, these numbers could make GLP-1s very effective anti-suicide treatments, without the often crippling side effects of lithium and other therapies.

Neuroinflammation, Alzheimer’s, and Cognition

Emerging research is also showing promise for GLP-1 drugs in treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. This is consistent with research suggesting that these drugs broadly reduce neuroinflammation, which may also be a mechanism through which they improve anxiety and depression and reduce suicidality. In addition there is substantial research indicating neuroprotective effects of GLP-1RAs.

Novo Nordisk is currently running two large Phase 3 trials to investigate the effect of GLP-1 drugs on Alzheimer's disease, based on early data suggesting reduced neuroinflammation, improved cognition and function, and enhanced memory, as well as trials in which GLP-1 drugs appeared to substantially reduce dementia rates in diabetes patients. Results from the Alzheimer’s trials are expected in late 2025.

A retrospective patient record study has shown a 48% reduced risk of dementia with semaglutide and reductions in cognitive deficits.

Pain

GLP-1s are also being investigated for osteoarthritis pain and disease progression. Any potential applications for pain reduction are highly relevant for OUD populations as they may reduce demand for chronic opioid pain management.

All-Cause Mortality

Additionally, numerous studies have shown large reductions in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes and more data will be arriving every year as these blockbuster drugs are used by larger and larger populations. Similar studies on mortality in obesity patients will likely arrive in the next 6 months.

Substance use disorders often contribute to cardiovascular events and mortality. This may be another positive factor for clinicians when selecting appropriate treatment for a patient with cardiovascular risk and a history of smoking, excess drinking, or other SUD.

As importantly, GLP-1 driven improvements in morbidity and mortality across so many conditions and patient populations strongly impacts the overall risk-reward calculation for prescribers considering a GLP-1 for a patient with SUD. While we do not yet have large-scale RCTs for GLP-1s for addiction, there may be so many other benefits to healthspan and mental health that for many providers, the overall risk of not prescribing these drugs as an adjunctive treatment may be higher than the relatively low risks of prescribing them.

Open Questions and Challenges

Price— Cost is currently a major obstacle as the sticker price of these drugs in the US is around $1,000 a month and insurance does not always cover the drugs for obesity. Insurance companies do not yet cover GLP-1s for being overweight (but not obese) nor for addiction. In most states, Medicaid will not cover GLP-1s for obesity though some doctors are finding ways around this by prescribing Ozempic rather than Wegovy. It’s possible this will change as more indications are added, like the recent FDA announcement of a new Wegovy indication for heart disease. To avoid dramatically worsening socioeconomic and racial health disparities, we need federal interventions that make GLP-1s available at affordable prices for everyone (the drugs cost only about $5 to manufacture a month-long supply). Taking steps to ensure equitable access for specific populations will not significantly reduce financial incentives for pharma companies to continue developing better versions of these treatments. Liraglutide is expected to become available as a generic in the summer of 2024, but it requires daily dosing and is generally less effective and shows fewer mental health benefits than the newer GLP-1s. That being said, liraglutide was used successfully in the small trial at Penn for opioid cravings, discussed above, and as a generic it may be a more affordable option in some situations. And with more GLP-1s expected to enter the market soon, there will be downward price pressure over the next few years.

Duration of effect— this is a key question that has not yet been studied in retrospective or prospective trials on addiction. Do the GLP-1 anti-addictive, anti-craving effects persist to the same extent that the anti-hunger, anti-obesity effects persist? In general, patient reports indicate they do. However, there are some patients who indicate that the effect of reducing alcohol consumption has partially lessened after 6-9 months of GLP-1 use. Duration of effect questions will eventually be answered in long-term RCTs but there may also be short-term opportunities for more granular retrospective studies examining this question. The immense scale of GLP-1 prescribing opens up a number of opportunities for well-powered retrospective research on narrowly targeted questions and rare events.

Nausea— initialization onto GLP-1 therapies can cause significant nausea. For patients who are beginning abstinence, GLP-1 nausea combined with alcohol or opioid withdrawal symptoms could lead to treatment discontinuation. Even patients who are not in withdrawal are highly sensitive to withdrawal-like symptoms and may misinterpret nausea as the beginning of opioid withdrawal. Fortunately, ondansetron plus metoclopramide has shown efficacy in reducing nausea from GLP-1 initialization and ondansetron is frequently prescribed by physicians for patients initiating on GLP-1s. This could be a good option to increase success rates for GLP-1 SUD treatment.

Human Trials in Progress

There are a number of clinical trials currently underway or being planned for GLP-1s, including a trial that Novo Nordisk just announced of Wegovy and alcohol use / liver disease. The majority of these studies focus on alcohol consumption, but there are also studies for opioids and nicotine being initiated. Large-scale trials for methamphetamine are urgently needed. A list of ongoing studies is in the Appendix at the end of this article.

Human Trials That Could Advance Practice in the Near-Term

Beyond the trials in progress listed at the bottom of this article, there are a number of study questions which we believe could rapidly advance our knowledge for important use cases in the near to mid-term and bring GLP-1s into the clinic faster. Crucially, pharma companies are not and will not pursue indications for GLP-1 drugs for addiction because they avoid studying unstable populations due to reputational risk and market-size uncertainty. While we believe they should be required to fund or run research for these types of indications, we must act now, with or without them.

More important than any specific study, however, is the need for strategic study design and selection. We believe there should be a concerted field-wide effort to design studies that can answer gating questions for real-world GLP-1 deployment for addiction: what do clinicians need to know and see to increase confidence in using GLP-1s for patients with SUD or SUD risk? What studies can be completed in a 6-9 month time period that can improve clinical practice quickly?

To reiterate, the opioid crisis is a national health emergency and should be treated with the urgency and strategic focus it deserves. Like COVID and HIV, every month of delay in bringing effective treatments to patients at scale means thousands of avoidable deaths. Urgency means gathering actionable evidence as rapidly as possible while preparing to deploy at scale. Operation Warp Speed is an excellent model for how to do this well. Given the vast scale of deaths from addiction, the number of lives that could potentially be saved by accelerating deployment of GLP-1 could be many times larger than the number of lives that were saved from the acceleration of COVID vaccine deployment. Stigma against patients and crisis fatigue are the only reasons that deaths from addiction are not treated with the same urgency as deaths from novel infections.

Tirzepatide or Semaglutide Monotherapy for Opioid Use Disorder

Is tirzepatide or semaglutide monotherapy effective for OUD? The Penn group mentioned above will be studying semaglutide for OUD in combination with methadone or buprenorphine. Combining these treatments makes sense as there are early indications that the combination will perform better than the individual treatments alone. However, if our goal is to significantly alter the course of the opioid crisis, a monotherapy trial is equally as important.

Even if GLP-1 monotherapy is found to be less effective for opioid cessation than a combination therapy, it has the potential to reach vastly more patients and reach them at earlier stages, including the high percentage of patients who have refused existing medication options. Due to massive and persistent cultural and patient resistance and restrictive regulations, opioid-based OUD treatments like methadone and buprenorphine are used by a small fraction of people who could benefit from them. To reach more people, we need non-opioid based treatment options with easy initiation and improved side effect profiles, like GLP-1s and non-addictive painkillers.

For example, an effective GLP-1 drug could serve as an excellent option for patients who may be in the early stages of developing a dependence and would have a low likelihood of being prescribed methadone or buprenorphine. For OUD in particular, since fentanyl dramatically increases the rate of accidental fatal overdose compared to heroin, we need medical options that can be used much earlier in the course of an addiction. Without this, we cannot succeed in reducing overdose deaths at a meaningful scale. To conduct an ethical outpatient monotherapy study, it may make sense to recruit patients who are resistant to or unable to initiate onto opioid-based OUD treatments.

Update: CASPR has launched a coalition to pursue large scale clinical trials of GLP-1s for addiction. Please be in touch if you are interested.

Tirzepatide or Semaglutide Monotherapy for Methamphetamine Use Disorder

There are no FDA approved medications for stimulant use disorder and the number of overdoses from stimulants has risen dramatically in the past 5 years. Short and long-term human trials for with GLP-1s for methamphetamine and cocaine should be a top priority.

GLP-1 Assisted Induction onto Buprenorphine

Does a semaglutide or tirzepatide injection (given at first visit and, optionally, ongoing) increase the success rate for induction onto buprenorphine? It may be helpful to provide patients with an optional ondansetron prescription for GLP-1 induced nausea, along with typical supports like clonidine and clonazepam once withdrawal begins.

Short-Term GLP-1 Co-Administration for MOUD and MAUD in Clinics

Does semaglutide or tirzepatide (given at first visit and ongoing) along with existing MOUD or MAUD increase success rates over a 3 month period? This could potentially be run as a single study with the induction trial proposed above, however we would suggest that results be published in two phases so that the very short-term induction data is not held back while waiting for success rate data.

Likelihood of Accepting Treatment of GLP-1 vs Existing MOUD Options

Does offering semaglutide or tirzepatide as one of the options for AUD or OUD treatment increase the likelihood of patients accepting treatment vs only offering existing therapies like naltrexone, buprenorphine, or methadone? The trial would randomly include or not include a GLP-1 option when proposing treatments to patient populations that have high rates of treatment refusal or reluctance. For example, patients with signs of AUD who do not consider themselves “alcoholics” may be willing to accept GLP-1 treatment because of the lack of stigma surrounding the drug and the other medical reasons they will be able to tell loved ones about why they are taking the medication. There are many ways to design studies to test this, but the core of the question is whether GLP-1s are able to dramatically expand the number of patients that will accept treatment. Even if GLP-1s have lower efficacy than an existing treatment (and there are indications that they may have higher efficacy), if they can reach many times more people, the overall public health impact would be massive.

GLP-1 to Enable Reductions in Methadone Dose Size

Does semaglutide or tirzepatide (given at first visit and ongoing) facilitate a reduction in dose or sustainable termination of methadone for patients currently on MMT for OUD?

GLP-1 Assisted Transition to Suzetrigine or Other Non-Addictive Painkillers

Does semaglutide or tirzepatide (given at first visit and ongoing) increase the success rate of transitioning chronic pain patients from opioids to suzetrigine, aka Vertex VX-548? This will likely require FDA approval of suzetrigine / VX-548 (potentially by Q1 2025) before an ethical study design is possible, to ensure long term access to suzetrigine for successfully transitioned patients.

GLP-1 for Repetitive Negative Thought in Depression and Anxiety

Does semaglutide or tirzepatide reduce rumination and repetitive negative thought patterns in people with anxiety and depression? Mindfulness training, which has shown some effectiveness in SUD treatment, is often oriented around disidentification with repetitive or ‘addictive’ thoughts.

Retrospective Studies

Well-powered retrospective studies are possible with GLP-1s because of the scale of current prescribing. We believe studies on these topics would be very valuable for policy and practice:

Mortality rate for patients with OUD or AUD history after initiating on GLP-1s vs other medications for T2D or obesity.

Lung cancer rates after initiating on GLP-1s vs other medications for T2D or obesity.

Physical injury rate (broken bones, wounds, etc) after initiating on GLP-1s vs other medications for T2D or obesity. Injury rates may decline secondary to substance use reduction and weight loss.

Alcohol related liver complication rates after initiating on GLP-1s vs other medications for T2D or obesity.

The Future: GLP-1s With More Muscle That Can Last All Year

As can be seen in the anxiety and depression data above from Epic Research, each new generation of GLP-1 seems to have stronger positive effects on mental health. This is consistent with patient reports, which are generally more positive about mental health benefits for Zepbound (tirzepatide) than for Wegovy (semaglutide). Several new and even more effective GLP-1RAs are expected to reach the market in the next few years that may bring additional anti-addiction or mental health benefits. Novel GLP-1s are also in development that have much higher high blood brain permeability which may result in different effect profiles.

Also exciting for addiction is the potential development of longer-lasting GLP-1 treatments. Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro, and Zepbound are currently injected weekly and indefinitely, which, while much better than daily dosing, still requires a high level of patient commitment to maintain. However, Novo Nordisk's chief scientific officer has suggested that they are investigating a long-acting GLP-1 drug candidate that would require administration once a year rather than once a week. The implications of such a development for addiction treatment, where treatment adherence is often the primary obstacle, are very significant.

While 73% of Americans are either overweight or have obesity, there are open questions about the use of GLP-1s in people who are not overweight— will these medications cause excess weight loss and, in particular, excess muscle loss? Ongoing studies in conditions that are less obesity correlated, like Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, may help answer these questions in ways that may be applicable to normal weight patients with substance use disorders. Additionally, a new GLP-1 candidate, pemvidutide, has recently shown weight reductions in a Phase 2 trial with a lower percentage of muscle loss compared to other GLP-1s. And in 2023, Eli Lilly acquired Versanis for their drug candidate bimagrumab, a monoclonal antibody that appears to be effective in preserving muscle mass during weight loss. For lower weight individuals, could there eventually be GLP-1 class drugs that do not cause weight loss?

Prescribing of GLP-1s for SUD Based on Current Evidence

As a clinician, family nurse practitioner Luba Yammine, PhD, MSN, sees patients with substance use disorders, including many who smoke.

She couldn’t help but notice something surprising when she prescribed a particular class of medications to treat patients with type 2 diabetes.

“All of a sudden they’d quit smoking,” Yammine recalled in an interview. “That sort of prompted my dive into the literature.” JAMA Medical News

While more RCTs for GLP-1s and addiction are needed and underway, we believe there is already substantial evidence that these drugs are effective in reducing addictive drive for a large percentage of patients. Individual physicians across the country as well as at facilities like the Caron Treatment Centers are already prescribing GLP-1s for patients with AUD and OUD. Patients are widely reporting that their doctors are willing to prescribe GLP-1s for substance use disorders upon request, reflecting the broad safety of the medication class.

The positive safety profile, combinability with existing medications for SUD, and holistic health benefits, will lead many clinicians and patients with SUD will try a GLP-1. Until an FDA indication is achieved, wide use will be constrained by cost and insurance coverage for patients who are not also eligible for an on-label indication.

GLP-1s Are Already Used by More People with AUD Than Legacy SUD Treatments

Crucially, GLP-1s already have an established history of use in patients with substance use disorders, simply because such a large percentage of the population is taking a GLP-1 for other conditions.

Meanwhile, adoption of existing medications for SUD is very low, particularly for AUD:

“AUD is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity, but compared with other chronic diseases such as cancers, hypertension, diabetes and depression, there is a very small number of US Food and Drug administration (FDA)-approved medications for AUD (acamprosate, disulfiram and naltrexone). These drugs also have low uptake (less than 2% in the USA) due to several factors, including patients’ reluctance to seek treatment, lack of addiction training among healthcare providers and considerable stigma surrounding AUD and addiction.” - Lorenzo Leggio, et al, Nature Medicine, December 2023

Based on the percentage of people in the United States with alcohol use disorder (11% or ~29.5 million) and the number of people who have received medication for alcohol use disorder in the past year (624,000) and the number of people taking GLP-1 drugs (7 percent of American adults or 18 million), we roughly estimate that more than 3 times as many people with AUD have been incidentally prescribed a GLP-1 in the past year than have been prescribed a medication that is FDA indicated for alcohol use disorder (~2 million vs 624,000, and these groups may overlap). If you imagine a public health campaign to get more people onto AUD medication, it would be a stunning achievement if you were able to more than triple the usage rate over 5 years and that may be what has already happened inadvertently. If GLP-1 use continues to rise as expected, we may be able to see positive trends in alcohol-related public health statistics in the next 2-4 years.

In terms of opioids, reportedly 22.3% of the 2.5 million Americans with OUD have received treatment with an OUD indicated medication in the past year (though some estimates put the number of Americans with OUD at ~7 million). Using the 2.5 million estimate to be conservative, that works out to 550,000 people with OUD receiving indicated OUD treatment and 174,000 people with OUD being incidentally treated on GLP-1s.

If you believe that GLP-1s are likely addiction-reducing, they would already be the most widely used medication class that reduces addictive drive in people with SUD. This also means that tens of thousands of SUD patients currently receiving treatment are already receiving both GLP-1 and indicated SUD treatments, establishing an important track record of safe monotherapy and combination use of GLP-1 in these populations.

We Know Enough to Pivot Towards This Opportunity

When mRNA vaccines were proposed and funded for COVID, they were an untested technology being developed for a novel virus.

“Economists preparing recommendations to the White House on allocating funds towards different COVID-19 vaccine methodologies received feedback from some corners that investment plans positing a possible role for mRNA were fanciful.” - Tim Hwang at IFP

Despite the very real possibility that mRNA vaccines might not work, the magnitude of COVID’s threat was enough that Operation Warp Speed invested heavily to fund and rapidly accelerate large-scale testing and deployment. Less than a year later, over a hundred million mRNA vaccine doses had been produced and distributed. The threat was real: in 2020, COVID caused 450,000 deaths. Meanwhile, annual US deaths from opioid overdose are 109,000 per year, deaths from excess alcohol use are 178,000 per year, and deaths from smoking are 480,000 per year. The scale of annual deaths from SUD is far higher than the worst year of COVID and it happens every single year. And because overdose deaths affect so many young people, the annual years of life lost to SUD are far higher than even COVID’s peak.

GLP-1s have already demonstrated a track record of safety and mortality reduction that can benefit a large percentage of the population, many of whom have a substance use disorder. Small trials, reports from patients and clinicians, and retrospective studies all point to a powerful anti-addictive effect. Additional trials of GLP-1 for addiction will add confidence, but there is already far more evidence of GLP-1 efficacy for addiction than mRNA vaccines had for COVID when Operation Warp Speed was launched. And pursuing mRNA vaccines at full speed did not stop the government from also pursuing traditional vaccines and investigating other covid therapies, just as the field of addiction will continue to pursue improvement and expansion of use for existing medication classes.

If we allow ourselves to truly recognize the scale of the numbers above, the deaths from addiction that happen year after year after year, and if we believe that GLP-1s have a high likelihood of efficacy and are positioned to reach a far larger percentage of SUD patients than existing medications, we should take coordinated action now. Funding should be poured into both rapid short-term and longer large-scale trials and federal staff should facilitate bureaucratic processes to help trials begin as quickly as possible. There is no reason to wait. Accelerated testing and deployment could save a simply massive number of lives over the next two or three years if trial results continue to be positive. If new trial results are negative, we will pursue other avenues. But these potentially preventable deaths deserve as much urgency as those threatened by novel viruses. And with addiction, more than any other disease, the number of deaths averted captures just a piece of the devastating cascade of downstream consequences that tear apart families, communities, and entire countries. The return on investment to society of addictions avoided or resolved is tremendous.

What we should not do is take a wait-and-see position, hoping that research groups will come along to propose and scrape together funding for long-term trials that may not give us actionable results before 2030. Imagine what could be accomplished if we brought together the political will and urgency to put $300M– just 17% of the budget for Operation Warp Speed– into an urgent strategic initiative for GLP-1 addiction research, training, and deployment?

GLP-1 therapies may be the first realistic opportunity we have ever had to substantially, and permanently, reduce addiction throughout society and across substances. This would be a historic public health achievement and tremendously healing for the entire world. We owe it to ourselves, our families, and our communities to fully pursue this opportunity.

Authors

Written by Nicholas Reville with Zarinah Agnew, PhD.

CASPR charts by Johanna Einsiedler, MSc and Karam Elabd, MSc.

Edited by Will Schachterle, PhD, Tom Hudzik, PhD, Selin Kubali and Karam Elabd, MSc.

Contact: reville@caspr.org

Our Mission

CASPR is a new non-profit research and policy organization focused on opportunities for breakthrough progress towards reducing addiction. We have a mix of paid staff and volunteers. If you are interested in collaborating with us, please contact us through our website. We are particularly interested in partnering with clinicians and researchers in the field of addiction and folks with experience in economic and public health modeling.

APPENDIX: GLP-1 and Addiction Human Trials in Progress

Please be in touch if you are aware of other trials that are not listed below.

Alcohol Use

Participants will get a liver medication, NNC0194-0499, semaglutide, cagrilintide or "dummy" medicine in different treatment combinations. Which treatment participants get is randomized. The study will last for about 39 weeks.

Status: Recruiting

Double-blinded randomized clinical trial investigating the effects of subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo on alcohol consumption in 108 patients diagnosed with alcohol use disorder and comorbid obesity over a 26-week period.

Clinical Trial of Rybelsus (Semaglutide) Among Adults With Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD)

Status: Recruiting

This study is a randomized controlled trial of oral semaglutide among treatment-seeking individuals with AUD. The investigators will randomly assign 50 participants to receive semaglutide (titrated to 7 milligrams (mg) per day) or matched placebo for 8 weeks.

NCT05520775: Semaglutide for Alcohol Use Disorder

Status: Underway

This is an early-Phase II human trial using a randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging design to investigate the effects of semaglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, on alcohol-related outcomes in adults with alcohol use disorder. Presently there are 48 participants in this study and the estimated date of completion is April 2024.

NCT06015893 Semaglutide Therapy for Alcohol Reduction (STAR)

Status: Recruiting

This study will test the safety/tolerability and early efficacy of subcutaneous (s.c.) semaglutide at the dose of 2.4 mg/week or maximum tolerated dose (MTD) as a potential new treatment for alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Smoking and Nicotine Dependence

NCT05530577: Effects of Semaglutide on Nicotine Intake and Smoking Lapse

Status: Completed (Results not Reported)

UNC trial investigating the effects of an approved GLP-1 receptor agonist on nicotine intake and reinstatement in humans. Dependent smokers will be enrolled in a double-blind, parallel-arm trial with laboratory endpoints.

Semaglutide for Post-Smoking Cessation Weight Management

Status: Recruiting

U of Texas trial examining the effect of semaglutide 2.4mg on changes in body weight, body composition, and peripheral and central mechanisms that control appetite, satiety, and food intake in the context of smoking cessation.

Opioid Use Disorder

Penn State Study of Semaglutide for OUD in Combination with Methadone or Buprenorphine

Status: Recruiting

200-person study of semaglutide in combination with methadone or buprenorphine.

Status: Development

NIDA CTN Study lead by T. John Winhusen, University of Cincinnati

Semaglutide for Helping Opioid Recovery (SHORE)

Status: Development

Brigham and Women’s 12‑week pilot, double‑blind, placebo‑controlled, randomized trial to evaluate semaglutide in individuals with opioid use disorder who are newly initiating buprenorphine. The study will enroll 46 participants (approximately 23 per arm) to assess semaglutide’s effects on cue‑reactivity as well as its preliminary efficacy, safety, and tolerability as an adjunct treatment for opioid recovery.

This is the first I’m hearing of this, and it’s so exciting to see. Big fan of this page so far, too, as a current PGY2 considering a career in addiciton medicine. Looking forward to reading the other posts.