To Solve the Addiction Crisis, We Need Strategies That Scale

Better, more appealing medications for drug use disorders can drive population-level improvements.

Addiction is the leading driver of death in the United States

Drug overdoses, from opioids and stimulants, have surged in recent years and now cause about 109,000 deaths per year in the United States. Deaths caused by excess alcohol use are 178,000 per year and smoking deaths are about 480,000 per year. That’s a total of about 767,000 annual deaths from substance use disorders.

For comparison, at its peak, COVID deaths hit 450,000 a year and are now 90% lower. Cancer deaths per year are about 609,000 and heart disease deaths are 695,000. Both are lower than substance use deaths, and over 30% of heart disease and cancer deaths are caused by substance use, which makes the gap even larger.

This makes addiction the leading cause of death in the US, and at least in the top 3 worldwide, but the field receives less than 5% of the public and private research funding of cancer or heart disease. Pharma has virtually abandoned addiction due to risk aversion, the high cost of running trials, and market unpredictability. Most medications for addiction are decades old. The public must step up and demand better treatments.

Policy has failed to solve the crisis

Short and long-term efforts on the left and the right to address addiction through policy are floundering. While there have been large reductions in cigarette smoking over the past 50 years, there has been no progress reducing consumption of alcohol. Deaths from opioids, cocaine, and methamphetamines have skyrocketed.

On the political right, the drug war has been fought for decades and has failed to stop production or smuggling. Meanwhile, fentanyl has overtaken heroin as the dominant opioid. It’s cheaper than heroin and 40x stronger, making it extremely easy to smuggle and impossible to stop.

On the left, drug decriminalization with regulation, which works for cannabis and psychedelics, just can’t keep people safe when it comes to highly addictive drugs that cause overdose, such as opioids, cocaine, and amphetamines. Harm reduction and treatment access are vitally important, but as these efforts have expanded, overdose deaths have still continued to rise.

The problem has reached a point where I think both the left and the right may be ready to admit (at least privately) that their side doesn’t have the answer. This may open up an opportunity to change directions.

And yes, there are things we could do to improve policy, increase treatment access, and to push more patients into treatment, but we are already running up against substantial resistance from patients, politicians, and the public. A massive $349 million study to implement best practices for opioid addiction, failed to reduce deaths.

There are other open societies with much lower opioid addiction rates, but these countries didn’t experience the American tragedy of Oxycodone and Oxycontin and they aren’t now awash in fentanyl as we are. There’s little reason to believe that European strategies designed for heroin dependency would be transformative for our problems of fentanyl and stimulants, which are dramatically different drugs. Would their approaches be at least a partial improvement over what we are doing? Likely yes, but we don’t have a political environment that will adopt them at scale anytime soon. And no city in America, no matter how liberal or conservative, has discovered a groundbreaking strategy, despite decades of experiments.

Fundamentally, we won’t solve this medical crisis without breakthrough medical solutions.

Existing medications are hitting a (low) ceiling of adoption

For a medication to succeed at broadly impacting public health, it must be appealing and effective, with low side effects. While it might feel out of place in a conversation about addiction, I think it’s useful to consider addiction medications as products, which they are. And the current products on the market are not selling well.

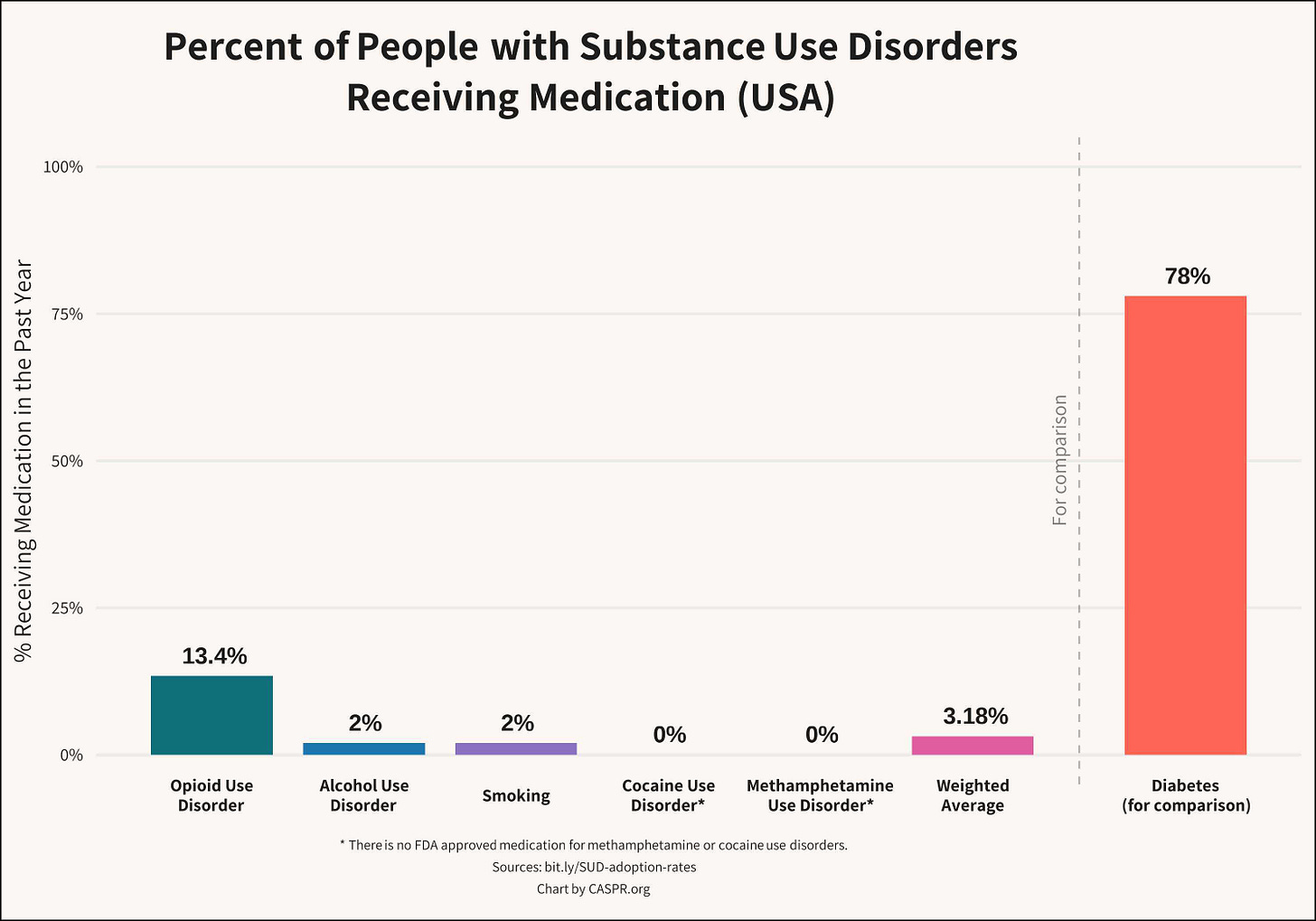

Existing medications for substance use disorder are very unpopular with patients. Only about 3.2% of Americans with a substance use disorder receive medication for their condition. That’s about 2% of people with alcohol use disorder, 13.4% with opioid use disorder (OUD), 2% for smoking, and 0% for cocaine and nicotine (there is no FDA approved medication for stimulant use disorder).

Efforts to expand access to OUD medications like methadone and buprenorphine are saving lives and there has been gradual progress, particularly for buprenorphine. We should continue to remove restrictions that prevent people from receiving these treatments. However, as we have seen with recent data from the X-Waiver removal, when restrictions fall, rates of adoption do not necessarily increase. Even if there was a miraculous shift and a sudden 50% increase in adoption, we would still be reaching just 20% of OUD patients. That would not be enough to shift into a virtuous cycle and solve the opioid crisis. Usage rates of medications for alcohol and smoking cessation have similarly plateaued.

Why are these life-saving medicines so unpopular? Existing addiction treatments face a number of obstacles including side effects, limited efficacy, patient resistance, stigma, low long-term adherence rates, and, for treatments like methadone, massive cultural resistance that has persisted for over 50 years, despite evidence showing the public health benefits of expanded access.

More effective and more appealing medications can sidestep the stigma and resistance that have stymied the field. To help a large portion of the SUD population, we need hit products.

Reducing addiction at a population level requires strategies that scale

We can save hundreds of thousands of lives over the next 10 years if we adopt a more strategic approach to addiction medicine. This means being honest about which paths have the potential to scale and pivoting our focus and resources towards those opportunities.

There is one long-term and two short-term strategies that I believe can make a major impact, and these are our current focus at CASPR.

Long-Term: More Medication Development

We should increase research funding for the National Institute of Drug Abuse by tenfold. This would bring public funding closer to heart disease and cancer and it would dramatically accelerate progress in the field. Even with this increase, addiction would still be far behind in total funding, since the majority of drug development spending happens in the private sector, and there is virtually no pharma activity for addiction therapies.

To address this, we should also create a reward pool, modeled on the PASTEUR Act and Operation Warp Speed, that would incentivize pharma companies who bring a successful addiction treatment to market. Advancing medicine to reduce addiction doesn’t trigger the culture wars around drug policy. It is truly consensus politics, focused on restoring agency individuals and families trapped by addiction.

Short-Term: Scale GLP-1s to Broadly Reduce Addiction Rates

GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro, And Zepbound (semaglutide and tirzepatide) show strong and broad anti-addictive effects, rapidly and dramatically reducing consumption of alcohol, opioids, cannabis, and other addictions. They also offer wholistic mental health benefits to patients, such as reducing anxiety, depression, and suicide attempts. These drugs also appear to have strong anti-inflammatory effects that may reduce the need for opioid painkillers.

GLP-1s can scale: they are extremely popular and well-liked drugs and could become the first blockbuster treatments for addiction. They are already used by millions of Americans with obesity or diabetes who also happen to have substance use disorders. However, the pharma companies developing these drugs are not studying them for addiction and have stated that they have no plans to do so. We need an aggressive strategy at NIH to run short-term studies on real-world efficacy and then scale adoption as quickly as possible to save as many lives as we can– we cannot wait for academic studies to slowly trickle in over the next 10 years. Here is our detailed review of the medical and strategic advantages of GLP-1s for addiction.

Short-Term: Make Non-Opioid Painkillers Accessible to Patients

Studies find that roughly 80% of people who have opioid use disorders (OUD) started with opioids prescribed by doctors and dentists, usually after procedures (1, 2). To address the ‘top of the funnel’ for opioid addiction, we should develop a policy framework to actively advance adoption of non-addictive, opioid-replacing painkillers. This will allow us to remove as many opioids from medical prescribing as we can without undertreating or suddenly cutting off long-term pain patients (which can cause overdoses as patients switch to the blackmarket).

Suzetrigine is a new opioid-replacing painkiller with similar efficacy to Vicodin (hydrocodone / APAP), but it will come to market at the end of this year as an expensive, patented drug that won’t be covered by insurance, forcing doctors to continue to prescribe unnecessary opioids. We should fix this market failure as soon as possible. We should also build new standards of care for doctors that will guide patients towards evidence-based pain therapies that are not medication based.

Additional Approaches

Beyond new medications, which we believe have the largest opportunity for impact, there are a few additional approaches we are studying which have potential to be deployed at scale.

First, using mobile phone apps, text, and automated calling can substantially increase adherence for existing addiction medications. Tools like this would not be expensive to make available for free to all providers and patients. CASPR has staff with a strong background in mobile technology development and we’re interested in partnering on approaches like these and supporting related, but more complex, contingency management projects.

Second, we believe better patient messaging can also be effective in preventing initial opioid addiction, if it speaks honestly and clearly. Existing opioid deterrent material, for example, is often dense text with vague warnings and a lack of statistics. What works for habit change is direct messaging, delivered at a decision moment, that provides clarity and treats the reader as an adult. We are developing a card insert to accompany opioid prescriptions for acute pain patients that would discourage overuse and encourage prompt disposal of remaining pills. Rather than saying “What’s more, your body may become used to a certain dose, potentially leading to addiction” we believe crisper statements like “6% of people who take prescription opioids develop an addiction” and “Do not let anyone under 18 keep this prescription in their possession” are more effective. We’re planning to run head-to-head trials vs existing materials to demonstrate superior efficacy.

Third, we, and many others, believe that opioid prescribing in dentistry is almost entirely unnecessary, even without new non-opioid painkillers. In 2016, American dentists were prescribing opioids 37X more often than British dentists. Dental prescribing has declined in recent years, but remains far above international levels, still around 20X the rate of Britain. Acute post-procedure dental pain can almost always be effectively treated without opioids. Bringing US dental prescribing down to international levels is low hanging fruit and could be accomplished with a targeted messaging campaign focused on dental clinics.

Our Focus is Scale

CASPR is a new policy and advocacy organization at the intersection of science and strategy. Our mission is to advance scalable opportunities that can substantially reduce addiction at the population level.

We receive no funding from industry, directly or indirectly. Moreover, we support taxation on pharma to fund addiction medication development as well as regulations that would require pharmaceutical companies to fund trials on therapies in their portfolio that the NIH deems promising for SUD.

We are working to advance possibilities for high impact in the short and long term. We think there is a tremendous opportunity to save lives and stop the devastating downstream consequences of addiction that tear apart families, communities, and entire societies.

Please be in touch if you’re interested in collaborating.

I think there are two other high impact pieces of advocacy I'd be interested to see more work on:

1. over the counter availability of naltrexone - still pretty much the most popular and effective existing medicine, not really abusable, negative impacts from overuse, but afaik no worse than other over the counter medicines, chemically similar to naloxone which is already available over the counter and often for free. Still not great adoption and mixed effectiveness, but wider availability still seems like an easy win.

2. improved test strips-not an addiction treatment per say but valuable harm reduction. Either increased availability of anonymous local lab testing, or research into scalable strip testing that is sensitive to concentration and not just presence of fentanyl/xylazine.